As you read this, I’ll be returning home from The Bass University in Chicago. I was there serving as an instructor, and one of my seminar topics was titled “Clear-Water Spinnerbaits,” a subject that’s very near and dear to me.

You see, when I began my career as a pro angler, spinnerbaits were considered tools for stained to muddy water conditions. Really the only time they were ever applied to clear water was when the cover was thick or the skies were overcast and breezy. Sure, there were exceptions. But that was pretty much the norm.

Luckily for me, though, a buddy of mine shared a concept he learned while observing Rick Clunn as he won the U.S. Open on Lake Mead in Nevada. The year was 1986, and Clunn’s winning pattern involved the use of a spinnerbait in calm, clear water conditions. If you’ve never seen Lake Mead, trust me, it is ultra clear. You can read the date on a coin in ten feet of water!

My friend, Chris Christian, served as a press observer in that event and he told me how he was blown away by Clunn’s ability to fool fish with such an abstract lure in water that clear — fish that were, at least in some instances, aware of his presence.

Clunn’s Concept

Like any concept, there are individual components that make up the whole — parts and pieces that work together to complete the puzzle. And Clunn’s concept was no different.

His discovery began with bass relating to isolated targets, in this case scattered bushes. Keep in mind that Lake Mead is a desert impoundment and visible cover is scarce, especially at low water levels. Clunn could see the bass relating to these isolated bushes, and in many cases, they could see him. So how he was able to coax them into biting a spinnerbait is nothing short of amazing.

Clunn discovered that by utilizing the cover to conceal his lure throughout most of the retrieve, he could make the fish bite almost at will. The key was determining the fish’s position as it related to the cover, then planning his cast so that the spinnerbait would remain concealed until it reached the target. Once it became visible to the fish, he would then accelerate the retrieve — making the lure appear as if it were trying to escape. And that’s precisely what triggered the bass to strike.

Clunn went on to explain that in many cases he could see the fish “feel” the lure approaching. Even though they couldn’t see it, through sonic vibrations they sensed its presence. And that’s what set them up for its appearance. When the spinnerbait would finally come into view, then zip away elusively at a high rate of speed, they would chase it down nearly every time.

Ingenious!

Why not another lure, you ask? Clunn did try other lures. But according to what he told Christian, if the fish had ample time to study those lures, they would lose interest. The spinnerbait, on the other hand, offered the element of surprise — it could race through the strike zone with stealth, and the fish simply couldn’t resist it.

Learning From The Master

After learning of Clunn’s exploits, I was eager to apply the concept to the lakes and rivers I was fishing. In Florida, we have tons of clear water. So finding situations for the technique wasn’t at all difficult. I spent months applying his clear-water spinnerbait strategy, and it worked as if I had read the instructions from a manual.

My first real success using Clunn’s concept came on the clear waters of Lake Ontario in 1990. It was the Canadian Open, and a large contingency of American anglers had entered the event. In fact there were more than twenty Bassmaster Classic qualifiers there, including Denny Brauer, Joe Thomas, Randall Romig, Tom Mann Jr., Rick Lillegard, Jerry Rhyne and others. Canada’s best also showed up. Competing were Bob and Wayne Izumi, Big Jim McLaughlin, Rocky Crawford and the Viola brothers.

In that event, I targeted both largemouth and smallmouth. I found the largemouth relating to isolated clumps of milfoil in the middle of a large, shallow bay. The water was clear and the bite was steady, so long as I maintained the right casting angles and rate of retrieve.

The smallmouth, on the other hand, were cruising over shallow main lake shoals in less than ten feet of water. To fool them, I had to use super-long casts and burn the spinnerbait right under the surface. It was so cool watching those big brown missiles sky upward to crash the bait.

A few months later, I won the (FLW) Golden Blend Diamond Invitational using the same patterns. Since that time, Clunn’s concept has helped me on many other occasions. It’s paid off in big tournaments on Okeechobee, Rayburn, Amistad, Lanier, Murray, West Point and numerous other major lakes — the technique seems to have no boundaries.

So long as the water is clear and the bass are holding on isolated targets, a spinnerbait has a good chance of working. It all comes down to presentation — that, and having just the right spinnerbait.

Sharing The Concept

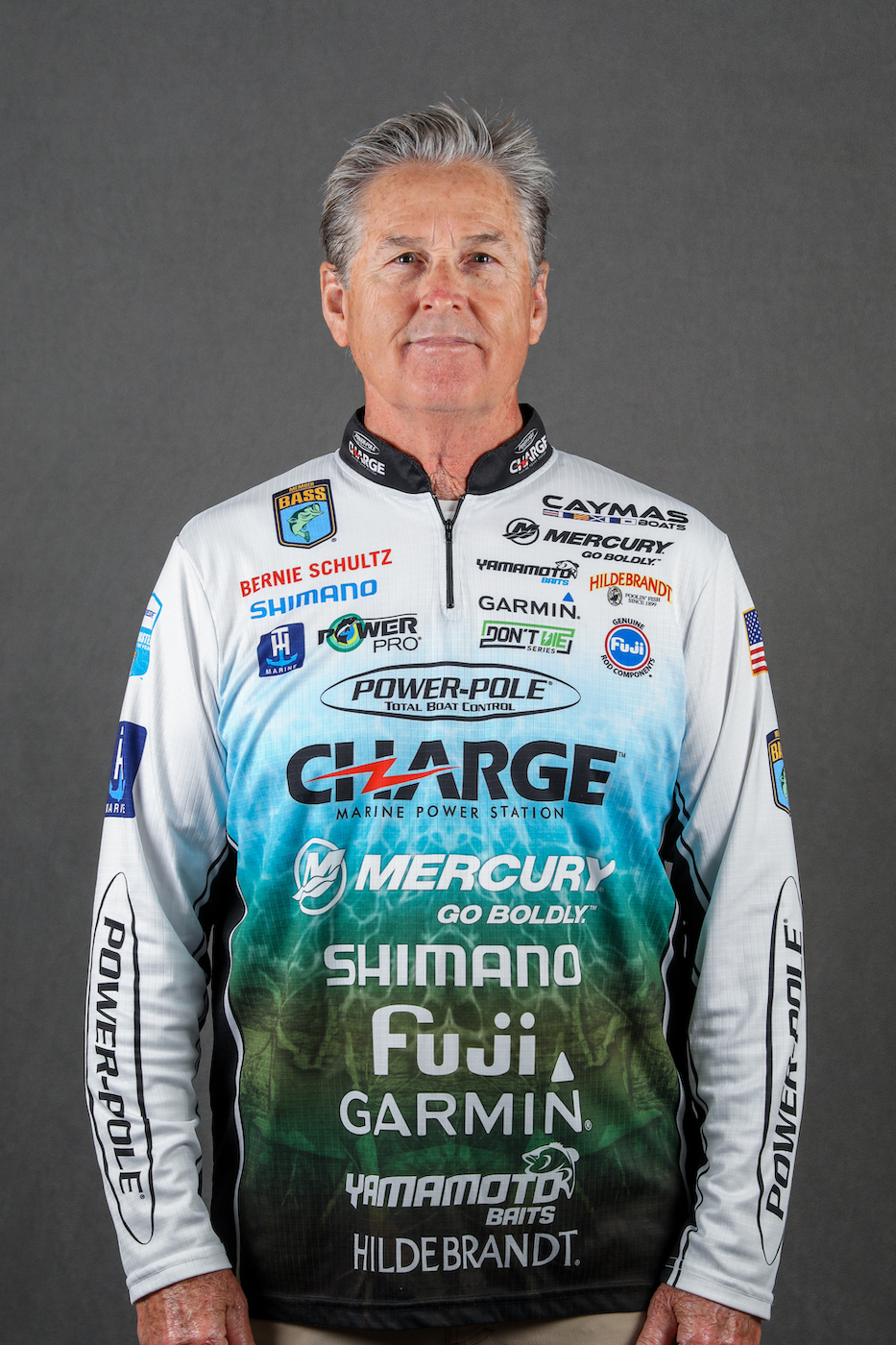

A few years after winning the Canadian Open, I became a columnist for Bassmaster Magazine. My series was called “Techniques Illustrated.” In each issue I profiled a top touring pro with his best technique, and one of my featured anglers was Rick Clunn on — you guessed it — “Clear-Water Spinnerbaits.”

Next time we’ll discuss how Clunn’s concept applies to aquatic vegetation. Plus, we’ll take a closer look at spinnerbaits and how combining the right blade configuration with lifelike cosmetics will work to your advantage.

Stay tuned!