Editor’s note: Read part 1.

In this final installment of how Ray Scott gave birth to tournament fishing, the curtains are pulled back. Close calls, near disasters and industry firsts are revealed

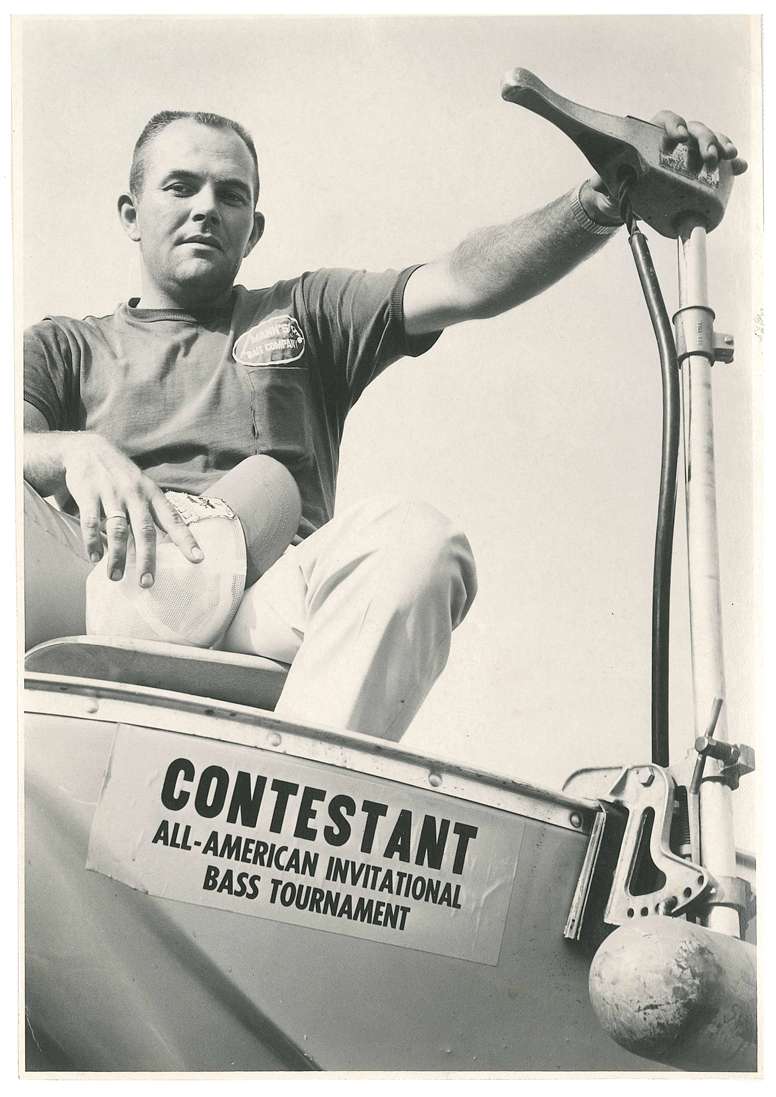

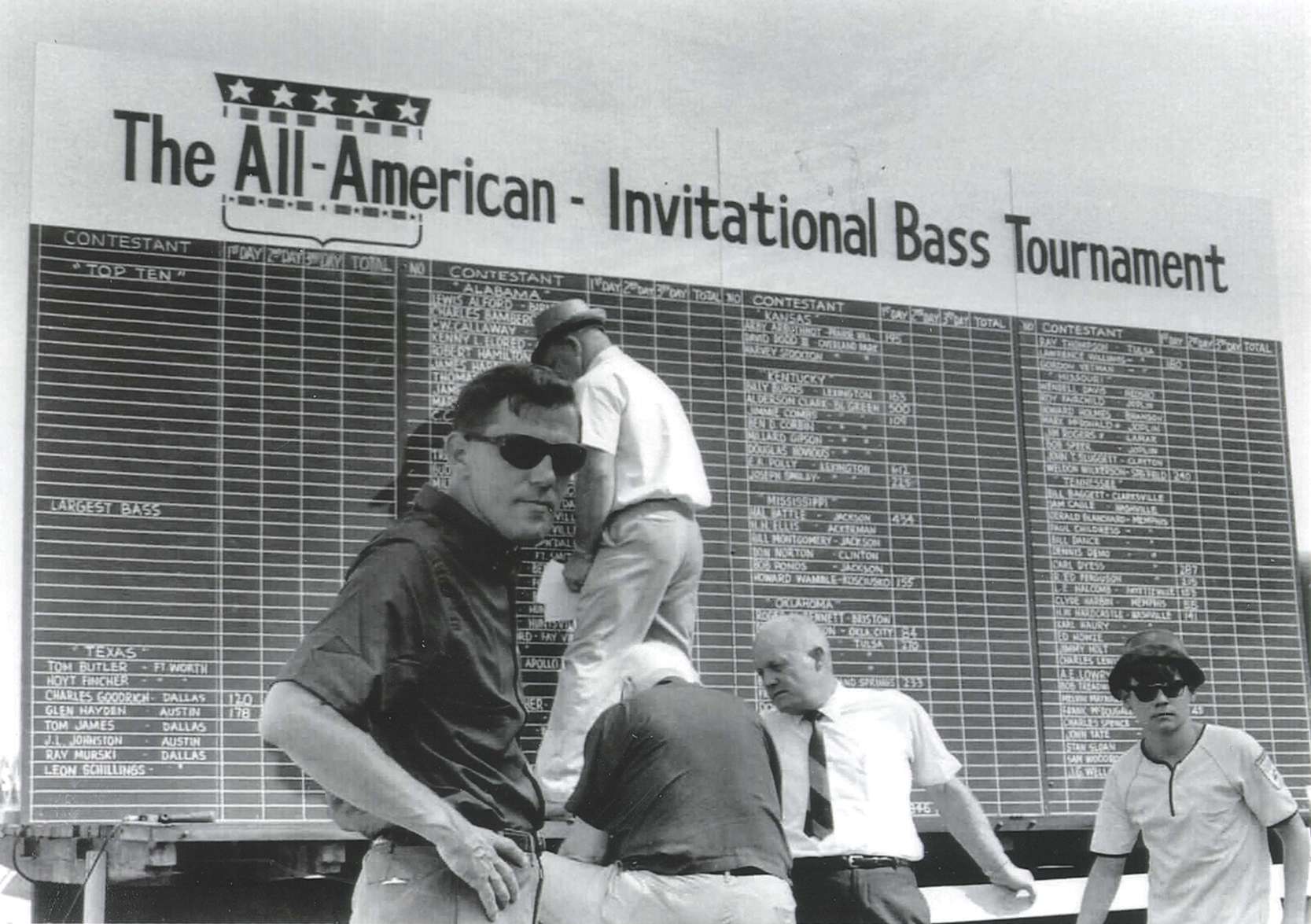

As a payoff for his tireless efforts and promotion skills, Ray W. Scott Jr. assembled a field of 106 anglers representing l3 states who were willing to bet their $100 entry fee in this “Test of the Best.” Behind the curtain, tournament director Scott was coiled in the fetal position. In the day, 1967, fishing contests were suspect. Well-intended chamber of commerce events resulted in black eyes where bad actors reportedly cheated to win. The contest rules were poorly written and slipshod enforcement was common.

Scott was painfully aware of the comments concerning the conduct of the rules officials at the World Series of Fishing. However, Scott’s biggest worry was the threat of a cheater. If it were possible, Scott would have put a Boy Scout in every tournament boat as a “policeman” observer. As a buffer, Scott paired contestants from different states or areas, feeling total strangers would play it straight.

Providing a level playing field, eliminating any possible hint of wrongdoing or weakness in the tournament rules strained Scott’s attention. To provide an equal start, Scott forbade any Beaver Lake fishing guide or dock operator to enter the All-American Invitational.

This boycott rule, perhaps, sidelined the best bass fisherman in the Ozarks: Glen Andrews, who was the Hy Peskin’s World Series champion, back-to-back in l965-1966. However, Andrews would inject his know-how into the All-American as Scott appointed him “chairman of the rules committee.” Scott still swears, “Glen Andrews probably is the best natural-gifted bass angler I’ve met or been in a bass boat with.”

Scott’s willingness to listen to Andrews’ advice and tournament experience no doubt influenced the drafting of the All-American’s rules — a Bassin’ Bible rule book still followed by most organized fishing tournaments today.

If we were to change the rules for a future All-American Invitational, the scoring system used in the inaugural event was not good. The winners were judged by a cumbersome point-scoring system rather than total weight in pounds and ounces. Here’s how the scoring rules played out.

Scoring will be determined by the point system. Points will be awarded as follows: Black bass (largemouth, smallmouth or Kentucky spotted bass), l0 fish total with three points credited per ounce. White bass (sandies, stripes or white lakers), 10 fish total and one point per ounce. Only 10 black bass and 10 white bass shall be credited each day for a total of 20 fish per tournament day.

Scott did receive suggestions for modification to the official rules. There was a daily 10-fish limit for black bass but not a size limit. Jimmy Holt, a fishing writer for the Nashville Tennessean newspaper, weighed in a 10-black-bass limit carried on a shoestring pulled from his tennis shoes. He scored a whopping 98 points — or 32.1 ounces — for the all-time smallest limit of black bass weighed in an official Scott-directed (B.A.S.S.) tournament. In the future, it was respectably decided that only black bass (largemouth, smallmouth, Kentucky spots or redeye bass) would be weighed in the creel.

Springdale chamber members and Arkansas wildlife officers pitched in to clean the tournament-caught fish to donate to a boys’ ranch and a local charity. At the time, unfortunately, the catch-and-release tournament concept was not on the minds of tournament officials or fishermen. But Scott and his future organization, B.A.S.S., would mount a “Don’t Kill Your Catch” movement to release tournament-caught fish alive.

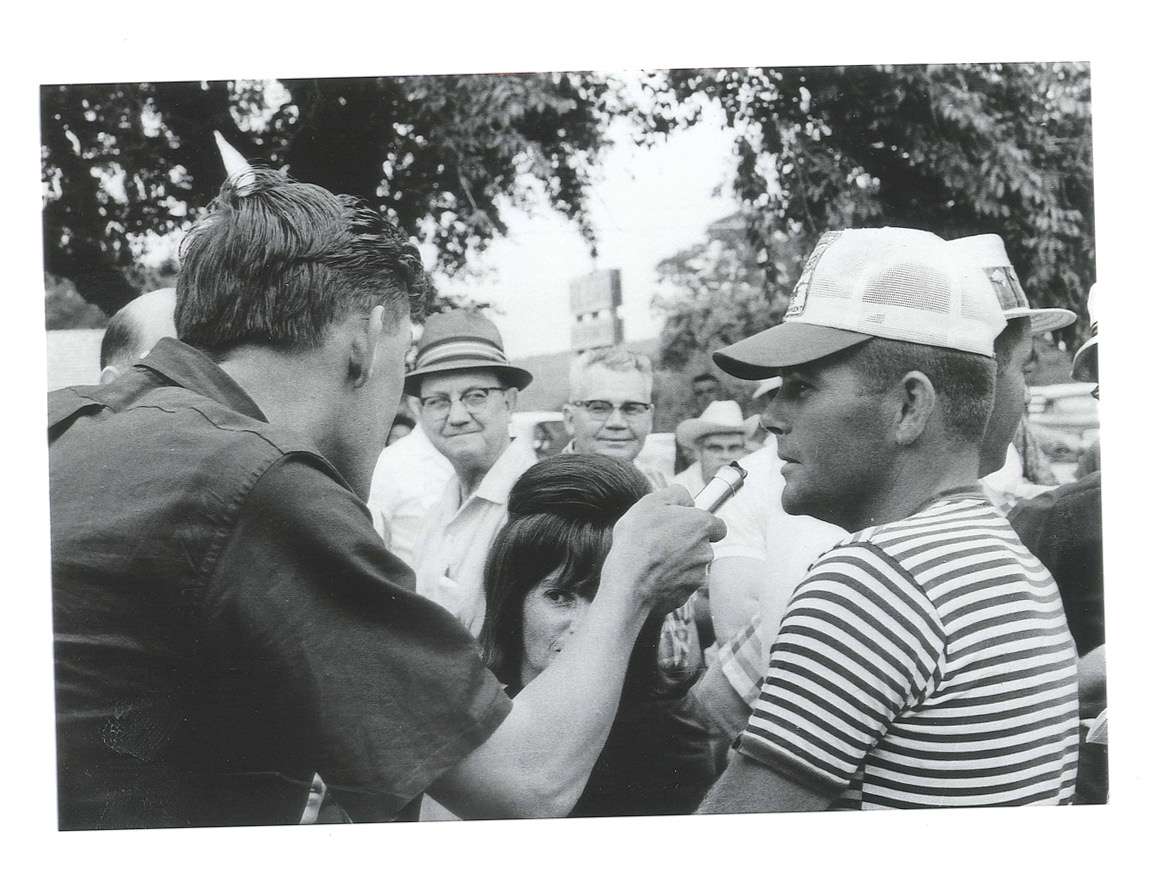

Sure, there were some warts to be expected on the first go-around of a big stage tournament, but for the curious outdoor scribe in the weigh-in crowd, it struck a gold-medal award. The post-weigh-in interviews were like a huge funnel; the angler’s proof in his creel poured in as pure how-to facts, and what dripped out the spout were the solid bassin’ tips of a proven bassin’ man. There, in naked review, were treasured bass fishing secrets. The discovery of the Texas rig, weedless plastic worm and slip sinker, reportedly the lure used by big, cigar-chewin’ Ray Murski of Dallas, Texas, who as a former Texas A&M lineman had welded a tractor seat on top his outboard motor to use as a pedestal chair.

The Texas angler jumped into fifth place after the Day 2 weigh-in, but this was turning into the all-Tennessee duel. Stan Sloan of Nashville was on top with 1,377 points (including a 10-black-bass limit of l4 pounds, l0 ounces). Close in his wake was Memphis’ Bill Dance with 1,211 points, helped by his nine black bass and 11 pounds, 9 ounces. B.A.S.S. trail history records that Dance on the early morning of June 5, 1967, caught the first black bass in the annals of the Scott bass tournament era.

Checked out at the Hickory Creek Dock, when the official at the dock fired the “go signal,” Dance gunned his 55-horsepower outboard toward the nearest shoreline cover and made a cast as the other boats in the flight ran past his spot. Dance set the hook and boated a keeper largemouth bass with his competitors’ wakes still in sight.

Any keeper fish in the livewell played like an ace in the hole in this game. Leg-long lunkers were out of the question. Holt’s stringer proved that point. E. R. Polly, a Lexington, Ky., angler, tricked a 3-pound, l3-ounce “lunker” on a Bill Stembridge Fliptail worm in the Rocky Branch area. The same general area produced a 3-l3 “heavyweight” for Tulsan Wes Littlefield on a Heddon Zara Spook topwater.

The action on topwater baits surprised some folks, who figured the best bet in the clear waters of Beaver would be the dependable plastic worm probing deep dropoff structure. But, there was Sloan, standing on the weigh-in stage, holding the champion’s hardware and revealing he spent all three days of the tournament throwing a Bomber Spin-Stick, a topwater plug with fore and aft spinners. Being in the right spot to target school bass action with the yearling size bass breaking on shad schools was key.

For “The B.A.S.S. Story” record file, Sloan rolled up l,860 points to clip Dance’s total of 1,682 points. Third-place finish fell to Alderson Clark of Bowling Green, Ky., with 1,609 points, followed by Murski’s 1,486 points in fourth and Tulsa’s Wes Littlefield in fifth with 1,455 total. The other Top 10 finishers in order were: Carl Dyess of Memphis, Tenn.; John Tate, Memphis; Troy Anderson, Little Rock, Ark.; Glen Wells, Madison, Tenn.; and J.L. Johnston, Austin, Texas.

Even before holding the 5-foot-high champion’s trophy, Sloan attracted a lot of attention in the boat parking lot at the Holiday Inn. Sloan’s Boston Whaler bass boat was rigged opposite to most. Rather than position the electric trolling motor on the craft’s stern, Sloan has his Silvertrol maneuvering electric kicker on the boat’s bow. Sloan’s clever reasoning: “It’s a lot easier to pull a chain along than try to push it along.”

Not surprisingly, many of the bystanders heeded Sloan’s example, and bass boat rigging from stern to bow changed overnight. Today, the bow-mounted, foot-controlled electric trolling motor provides hands-free operation for casting and, as a result, more casts and more strikes. So many bass fishing innovations materialized as the thinking and demands of the growing bass fishing public caught up to the winning ways of the pros on the Bassmaster tournament trail.

The $2,000 winner’s check had not cleared the bank before Scott was in high gear, planning his next tournament — the Dixie Invitational — at Lewis Smith Lake near Cullman, Ala.

Back in Montgomery, Scott marched into the office of the Underwriters Insurance Company, resigned his position, borrowed two desks from his former employer, moved across the hall and went into the bass fishing business full time. Scott hired his one-time high school sweetheart Sarah Smedley as his secretary and went to work.

However, bass tournaments were only the means to a much larger goal. The experience at Beaver Lake and the brotherhood of bassers represented by the Tulsa Bass Club and Memphis Bassmen put Scott’s brain in focus — another brainstorm was on the horizon.

Scott viewed the bass tournament anglers as seeds to be planted across the U.S. Bass Nation and sprouting up as local bass clubs. He would form an organization to lead the harvest. Scott said, “Bass fishing has so many elements. I think fishermen desire and will support and respect the resource. But, I need a name, a symbol to unite bass anglers nationwide, an opportunity to join together and become better bass fishermen.”

Scott recalled his visit with Uncle Homer and his gift with words. On the phone, as previously, Homer Circle listened intently to Scott’s query for a name for his planned fishing fraternity. Uncle Homer, on the spot, didn’t offer a suggestion, but suggested Scott call Bob Steber, the outdoor editor of the Nashville Tennessean newspaper.

Uncle Homer explained, “Bob Steber came up with the name A.P.E.S. for the group of fishermen, who celebrated the rites of spring each year — The April Piscatorial Endeavor Society.”

Scott recalls, “Bob Steber was having a drink in his office with Ben Corbin of Pedigo Lures pork rind company and said, ‘Give me an hour to mull a name over.’” An hour passed and Scott’s office phone rang.

“OK, Ray, here’s the name of your club. Call it the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society,” said Steber.

Scott’s immediate reaction: “Bob, that’s kind of long, ain’t it?”

“Yes,” said Steber. “That’s why folks and writers will call it B.A.S.S.”

Scott foresaw the value of B.A.S.S. as a symbol, something as respected as the American flag. He gazed upon a catalog rendering of a leaping largemouth bass in a Zebco fishing reel advertisement and sketched out the design of the B.A.S.S. patch — a blue and gold shield with the letters B.A.S.S. emblazoned over the leaping lunker bass, and Bass Anglers Sportsman Society spelled out.

What next? Scott needed the support of an active bass club. The Tulsa Bass Club, now headed by Don T. Butler, offered a perfect sounding board and solid creditability. That is, if he could get the Tulsa club on board.

Before an arranged club meeting at the Tulsa Trade Winds East hotel, Scott practiced his sales presentation on Butler. As they left the Tulsa airport in Butler’s truck, Scott picked Butler’s brain about the Tulsa club’s bylaws and membership guidelines and any dues. This prompted Butler to ask, “What would you charge a year for a B.A.S.S. membership?”

Scott figured for a moment. “What do you think about $10 a year for a membership, which will include [the] Bassmaster Magazine we’ll print every quarter?”

Butler’s answer was to reach into his shirt pocket, pull out a $100 bill and say, “How’s this for a lifetime membership?”

The short answer: “Pull over here and let me get a receipt payment book. Don Butler, you are officially the first member of the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society of America.”

A footnote: The first B.A.S.S. membership signed by Scott hangs in his office in Pintlala, Ala., dated Jan. 5, 1968.

Tulsa in early January can be bitterly cold, with deep-freeze winds blowing a gale. Being from the Deep South left Scott at a disadvantage and without a heavy topcoat. At the hotel meeting, Scott answered questions and made his pitch for the Tulsa Bass Club to join the B.A.S.S. movement.

The floor asked for private comments and requested for Scott to step outside. “I felt like a popsicle in a minute,” recalls Scott, who pressed against the sliding glass door, trying to hear the discussion.

One question stood out: “This sounds all good and optimistic, but how do we know Ray Scott can pull it off?”

“Because Ray says he’s going to do it.” The room turned to look at Butler, who added, “No more questions. Let’s vote.”

The show of hands gave the full support of the Tulsa Bass Club to get behind the organization of the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society.

But, from the startup in 1967 to late 1970, when the B.A.S.S. memberships started to roll in at $10 per member, time and money were focused into how to pay for new members’ mailings.

Butler encouraged Scott at every turn, and called regularly to ask, “How is it going, Hoss? What’s the membership now?”

Scott related he planned to drop a big mail promotion, but was turned down at the bank for a loan with the explanation, “If you were still in the insurance business, there would be no problem.” And, Scott discovered, “The post office won’t take an IOU to cover postage.” Butler didn’t say another word but “goodbye and good luck, Hoss.”

That afternoon, Scott’s phone rang with a Western Union agent on the line. “Mr. Scott, Ray Scott, you’ve got a money order here at the office. Can you come in today for a pickup?”

Thinking maybe it was an entry for the next tournament, Scott hustled downtown. Showing his ID, Scott waited for the agent to produce the money order.

“Mr. Scott, I’m sorry we don’t have this amount in house, but here’s a draft you can cash at the Union Bank.”

Scott was stunned. The check was for $10,000 dollars. He sputtered, “Who is this from?”

“Can’t give you a name, but the money order came from our Tulsa, Okla., office.”

No name. No explanation. No promissory note. But, $10,000 dollars in cold, hard cash. The only explanation? Butler riding to the rescue. Scott dropped the B.A.S.S. membership mailing, and in six months had the 10 grand back in Butler’s hands.

Scott’s B.A.S.S. organization was in a survival mode, too. By late 1968, the B.A.S.S. emblem was being worn by over 2,000 card-carrying members. The society was on the march, but Scott needed help to keep up the pace.

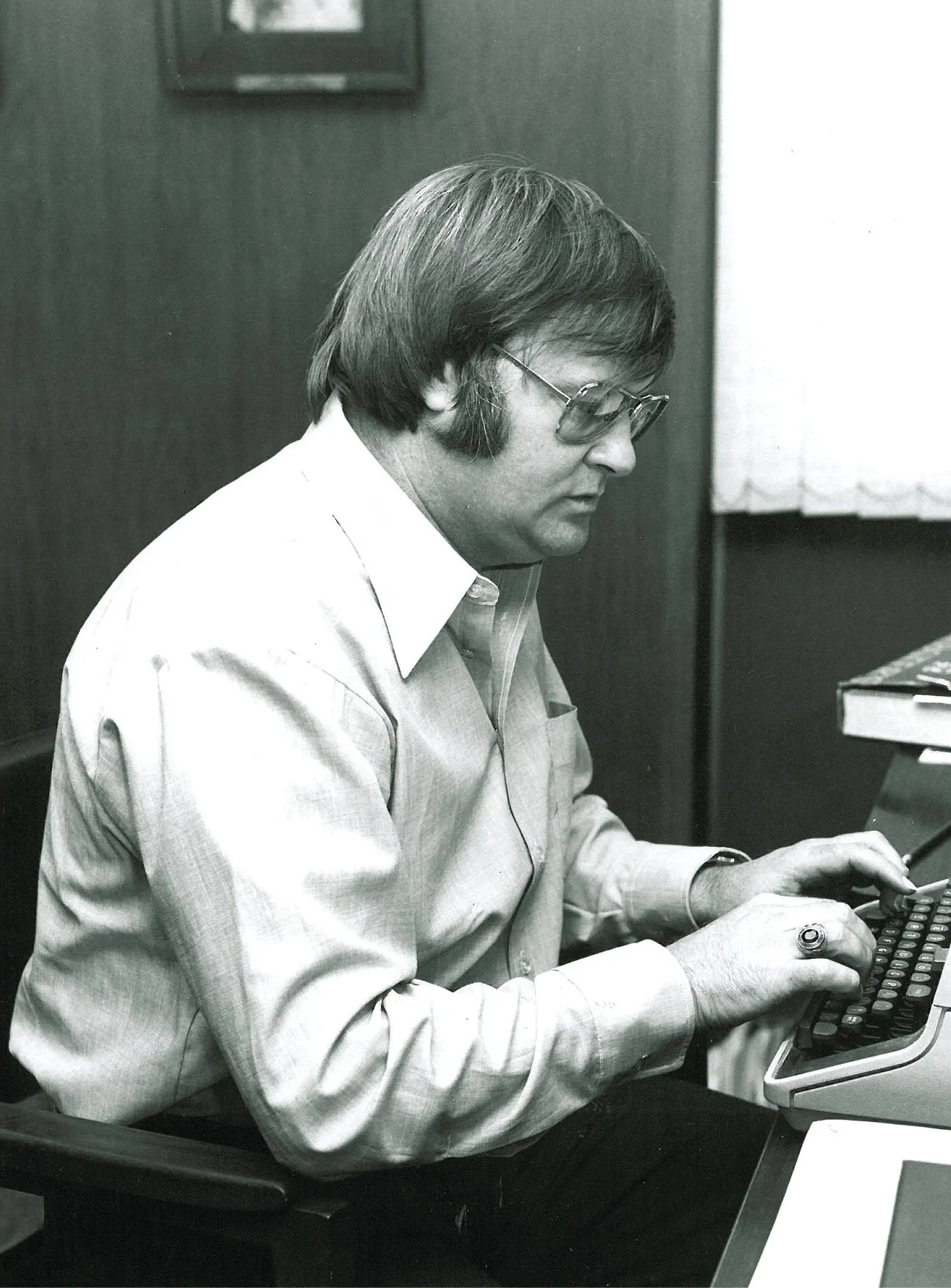

“I had too many oars in the pond,” explained Scott. “Just the B.A.S.S. tournaments were a time-consuming task, running here and there, keeping a handle on the membership mailings and getting bogged down as the editor of our upstart Bassmaster Magazine, for which my English and editing skills were sorely lacking.”

As to his grammar shortcomings, Scott openly joked about what his college professor at Auburn University remarked when Scott challenged the teacher’s grade of D-minus on a term paper.

“Mr. Scott, you didn’t deserve a mark better than the D-minus. Your writing and use of the English language is atrocious, but adequate to express your thoughts.”

The articles in Scott’s first attempt to edit as publisher of Bassmaster Magazine didn’t sing of flowery English prose, either. The hand-written pages submitted were often marked by a coffee cup ring stain, where the author had labored at his kitchen table to unwind his how-to techniques.

“There was no true editor, as such, to rewrite or clean up the copy”, recalls Scott. “A single thought or sentence might scrawl over a page or more of notebook paper. At one point, I told my office girl to grab some scissors, cut the article into some paragraphs and run with it.”

Despite lacking a polished writing style, the B.A.S.S. publication was loaded cover-to-cover with bass fishing facts — not glowing sunrises or travel book snapshots. Missing were the slick, four-color photos and well-honed narrative of the Big 3 outdoor magazines — Sports Afield, Outdoor Life and Field & Stream — but the B.A.S.S. offering was soon recognized as unique in the field. It was written by bass anglers, in a language spoken by bass fishermen, for the dedicated bass chaser.

My passion for the challenge of bass fishing didn’t wander off far from the tournament trail and his interest in Bassmaster Magazine. The “Bass Boss” himself stoked the flame, dangling the prospect of becoming the magazine’s editor. The two-party phone connection was frequent and long. He wiggled in the back door, calling Barbara Cobb, my wife, frequently, extolling the Southern lifestyle and the Old South charm of Montgomery, Ala., — “the Heart of Dixie.”

The 1969 Spring issue marked the editorial direction change as Scott wrote, “I’ll be fishing from here forward in the back of the boat. Your new editor, Bob Cobb, will be running things. Welcome Bob on board. He can read and write.”

“Write” — maybe — but the newspaper ink in my veins realized that “pickle-box file” held the true bassin’ stories waiting to be told. Opening the box unfolded a wonderland of fishing characters, much like Alice falling down the rabbit hole to meet the Tin Man or the Scarecrow.

There was George Walters, a carpenter by trade, who lived in Jackson, S.C., and spilled out his “fishing secrets so other B.A.S.S. members can learn from the pros.” As a matter of bass fishing profile, Walters staked a lot of weight on selecting a “good, trustworthy fishing partner.” He described his wife, Gladys, as the perfect example.

“My wife can back a boat, use a landing net, sure handed, and will clean our catch. And, in season she’s the best at turning the squirrels.”

For pure, unpolluted fishing savvy — the winning ways of the pros — that first effort under my thumbprint uncovered the early day master of the art of plastic worm fishing. John Powell, a former chief master sergeant in the U.S. Air Force, had retired to return to his home area in Montgomery. Growing up as a farm boy, Powell fished the Chattahoochee River and Jordan Lake to put meat on the family table.

In his career as an early star on the Bassmaster tournament trail, Powell earned a reputation as the “king of the shallow waters”. Despite the season or reason, Powell believed, “There’s always some fish in shallow, and they will bite.”

His notion of fishing depth was explained as: “If I can’t touch the bottom with my 6-foot rod, I’m fishing way too deep.”

Powell, for sure, was the grand master with a 6-inch Crème purple plastic worm on the line, hammering the shallow-water cover. But, it was the “Man with the Golden Hands,” Dance, who provided a four-step photo illustration on rigging the weedless Texas rig plastic worm as a centerfold in the magazine.

Dance finished a close runner-up to Sloan in the l967 All-American at Beaver Lake. Dance’s winning ways and fishing skill with the plastic worm rig prompted Henry Reynolds, outdoor editor of Dance’s hometown Memphis newspaper, to proclaim him blessed with golden touch in his hands to feel a slight worm bite.

From his first cast, Dance became a fishing force to reckon with, and without question dominated the early days as the sport’s first superstar.

Later, B.A.S.S. would publish a tell-all book by Dance on his secrets for plastic worm fishing titled There He Is — a phrase most bassers uttered when feeling a bass pick up a worm or the faint tap-tap signal.

B.A.S.S. publications not only heralded a new era in bass fishing, but a new language, as well. Fishermen in different areas had a common lingo, but its use not widespread. The terms used by tournament anglers had to be coined simply to convey the action. The foundation of how bass anglers communicate today basically was launched from the pages of Bassmaster Magazine.

The magazine chronicled the winning ways of the pros and revealed the hottest new lures and tackle favored by the top-ranked pros. Fishing tackle manufacturers soon realized this target market was ground zero in tackle sales and placed four-color advertisements, and they were willing to pay a premium for the cover positions.

Just as the NASCAR racing circuit brought safety and motoring innovation to the car-loving American public, the Bassmaster Tournament Trail provided the proving grounds for safer, more efficient and trouble free boating and fishing.

Singling out one species — the black bass — for tournament attention has brought about more biological interest and knowledge in and about bass and species management. Prior to the interest in bass fishing, biologists knew more about catfish, because of the commercial value, than about black bass.

Catch and release came directly from B.A.S.S.’s “Don’t Kill Your Catch” movement. As did the modern livewell system, humane fish handling techniques, lower tournament daily limits, slot-size management, radio fish tracking, motivation for clean water, and the list goes on and on. All of this was brought about by concerned, thinking bassmasters preserving, while tackling, the greatest fish that swims.