This month we celebrate the 50th anniversary of Ray Scott’s first bass tournament. Here are the behind-the-scenes details of the high-risk, high-reward efforts of the B.A.S.S. Boss and the handful of anglers willing to bet on the future of competitive fishing.

The smartphone is a wonderful innovation. Information at your fingertips, an encyclopedia of events and history in response to a simple question to the powerful oracles of our age: the voice recognition Internet search technologies.

“Is Ray Scott the man behind the sport of professional bass fishing?”

The automated voice will answer, “Yes, Ray W. Scott Jr. of Montgomery, Ala., introduced competitive bass fishing on June 5 to 7, 1967, at Beaver Lake, Arkansas.”

Editor’s note: See photos from Ray Scott’s first tournament.

On the surface, any fact checker will attest to Scott’s certification as the visionary who propelled the black bass to become America’s fish — replacing the Lordly Trout as the most coveted, sought-after sportfish in freshwater.

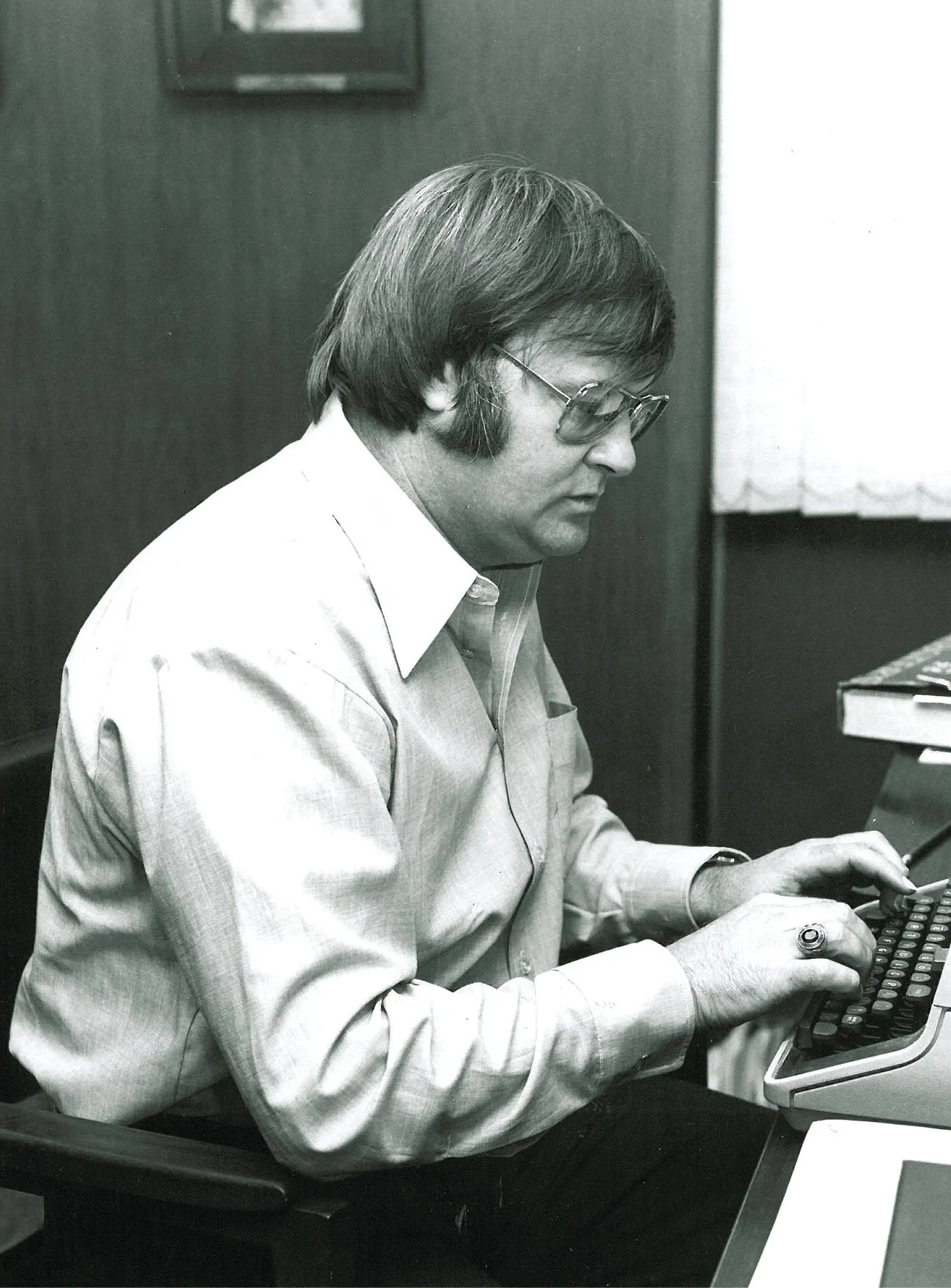

Scott, an insurance salesman at the time with a passion for bass fishing, used his know-how to prospect for potential insurance policy buyers to parlay four named fishermen on a 5 x 6 card file into the world’s largest fishing organization, with over 650,000 members at the high-water mark.

This is the story behind the headlines: How an addicted angler and a few dedicated followers revolutionized the fishing industry and turned cast-for-cash bass fishing into a mega-dollar business, a political force and a savior of the fishing resource, with a legal team of “Peg A Polluter” stopping cold offenders from dumping waste into public fishing waters.

Scott’s makeover of the bass fisherman from a beer-drinking, cane-pole worm dunker in faded overalls to today’s sponsor-logo-laden jerseys, high-powered bass boats and legions of fishing fans following their heroes on cable television programs is a public relations/marketing textbook lesson.

The message to bass fishermen, in the beginning, had in-your-face appeal: “If you piddle with perch, mess with musky or fling a fly for trout, you don’t qualify. We want a few good, hairy-legged bass anglers to join our cause.”

If you compel Scott to swear on a stack of “Fisherman’s Bibles,” he will surely admit to giving the good idea of competitive fishing a better foundation of tournament bass fishing. Credit belongs to Hy Peskin, a famed Sports Illustrated photographer, for spawning the idea in the late 1950s with his World Series of Sport Fishing. According to angling lore, Peskin, who photographed many of the era’s sports greats, overheard Ted Williams boast,

“There are over 20 million fishermen in the nation. It’s the greatest participant sport, and I’m the best.” This prompted a discussion of “Who is the best?”

As recounted, Peskin, who had never caught any fish, didn’t respond, but he saw an opportunity to capitalize on piscatorial pride. Peskin’s concept mirrored baseball’s World Series, putting fishing on a grand scale on a grand stage. Each state, Peskin dreamed, would have its own tournament leading to a regional championship to decide the anglers to compete in the World Series finals.

A grand plan, but Peskin, in truth, was a promoter, not a fisherman. Critics of the day said Peskin had little understanding of what actually made a fishing tournament work and that he instead depended on others’ advice to determine the rules and fishing waters and reportedly was “easily swayed in enforcing the tournament rules.”

If the fishing facts be known, bass tournament competition was birthed by Earl Golding, the outdoor editor of the Waco, Texas, Tribune newspaper. In 1955, Golding organized the first Texas State Bass Club tournament, and his statewide press coverage and reports sparked interest among Lone Star anglers. But, it was a Texas-based enterprise with few ripples beyond the Red River boundary.

So the big stage was set when Scott walked on the scene in 1967 with what became known as a “Brainstorm In A Rainstorm.” Chased off nearby Ross Barnett Reservoir by a perfect storm, Scott hunkered down in a Jackson, Miss., motel room to dry out. On the TV screen, an NBA professional basketball game caught Scott’s eye.

He wondered out loud, “Why can’t bass fishing generate this kind of sports coverage?”

And, as Ted Williams observed so keenly a decade earlier, “There are a million times more fishermen in this country than grown men in shorts playing a kid’s game.”

Scott continued to muster his thoughts while flipping the pages of an Outdoor Life magazine picked up off the motel nightstand. An article by Charlie Elliott about a new bass fishing gem discovered in the Ozarks — Beaver Lake — caught Scott’s attention. Located in northwest Arkansas, this newly hot lake on the White River chain was destined to soon overshadow the famed bass lakes of the Ozarks, like Bull Shoals and Table Rock, according to the magazine report.

Scott jerked straight up out of bed and exclaimed, “Yes, that’s the answer! It’s now or never. Outdoor Life’s readership of fishermen all over the country will be eager to come fish Beaver Lake.”

Outside, the rainstorm’s velocity seemed to peak, just as Scott’s own brainstorm started to spill out an idea, a vision, a dream to make bass fishing as popular as NFL football and, yes, create the “Super Bowl of Bass Fishing.”

Never one to sit on an idea to hatch it, Scott immediately phoned his insurance office in Montgomery to report he would be making some “sales calls” in Arkansas for the next week.

The first call was to the Arkansas Wildlife Department in Little Rock, seeking information for contacts in Springdale or Rogers, the two largest communities bordering Beaver Lake. Scott learned the Springdale Chamber of Commerce was the bell-cow ringing the publicity and promotion the loudest.

With great confidence and swagger, Scott walked out of the Fayetteville Regional Airport to meet a Springdale chamber representative the next morning, to present his idea for the All-American Invitational Bass Tournament, a name Scott came up with on the fly.

The chamber official, Lee Zarachy, greeted Scott warmly, eager to learn more about “the biggest event in fishing” soon to be staged on Beaver Lake.

Wanting to show his cooperation, the official asked, “Will your staff be joining you, and will you require additional rooms at the Holiday Inn?”

Scott smiled inwardly. “What staff? If I can pull this off, maybe I’ll need to hire a secretary.” He explained his staff was coordinating the All-American, for the present, from his Montgomery headquarters.

The board of directors of the Springdale Chamber of Commerce assembled to hear Scott’s announcement of plans to make Beaver Lake the center of the nation’s bass fishing world with a three-day, early June tournament, with the weigh-ins taking place in Springdale to attract attention and crowds to the city.

The chamber folks seemed ready to swallow Scott’s idea — hook, line and sinker — until the subject of co-sponsoring the All-American reached the table. Scott proposed a $10,000 budget to promote the event and lock in an estimated 100 bass fishermen needed to provide entry fees to pay a sizeable jackpot to lure fishermen.

The Springdale chamber wiggled off the hook, not sure if Scott was a slick-lipped promoter or maybe a con artist. But, while the chamber would not chance upfront money, a rent-free office in the back of the city’s Chamber of Commerce building was offered.

Despite the chamber’s thumbs-down vote, two members felt the All-American Invitational might represent a great spectacle and cast the fishing spotlight on Beaver Lake. Joe Robinson and his son Tub had sunk seed money into building a marina on the lake. They offered the War Eagle Dock as a possible launch point for the tournament, eager to draw attention to the new facility.

However, it was Dr. Stanley Applegate, a local physician, who most assuredly saved the All-American from a sinking demise. He pulled out his checkbook and on the spot wrote Scott a check for $3,500. He said, “If the tournament works out, you can pay me back, but if we fail — don’t tell my wife.”

“I won’t accept failure,” Scott told his new benefactor. “I’m driven to success rather than the alternative. You will get your investment back, trust me.”

“Trust me.” The words of a con man? In this context, it’s like the old proverb: “The higher up the palm tree the monkey climbs, the more of his ass is exposed.”

For sure, Scott was about to perform a high-wire act. At the time, the odds were on the side of Scott making a misstep and falling. One stumble and his dream would surely turn into a nightmare.

Among the outdoor press there was disdain for competitive tournament fishing. The purist outdoor writers felt strongly that the noble sport of hook and line was judged to be a contemplative venture — not a competition with nature.

Seeking to gain support for his idea, Scott sought out Homer Circle, a nationally known fishing editor for Sports Afield magazine who lived in nearby Rogers. “Uncle Homer,” as he was called by his outdoor colleagues, had a strong reputation for conservation, and he listened quietly to Scott’s best sales pitch.

Circle shook his head sideways and vowed, “I’ll make you a promise — a deal. I’m not going to write anything [positive] about your tournament, but I won’t write anything negative, either. Good luck, Mr. Scott.”

Later, Scott noted, “Uncle Homer had his strong convictions but seemed willing to give me enough rope to make the All-American work or hang myself.”

As a footnote, Circle would later write a column discussing his pre-tournament meeting with Scott and his promise to be neutral, then admitting the unshakeable belief that Scott would prove to be “a winner.”

About here is where this writer — Bob Cobb — of the Tulsa Tribune newspaper waded into the discussion of competitive bass fishing. By letter, Scott sent an invitation to the Tribune’s outdoor editor to attend a noon press conference the next day in Springdale to learn about “The Biggest, Most Important Happening In Bass Fishing History.”

Unknown to Scott, he tripped the trigger of another bass fishing addict, and I wanted to know more. At the moment, the need was now — less than 45 minutes before the day’s deadline for the Tribune’s sports section closed.

I got Scott on the phone and told him he had a decision to make. “Ray, I need to get a break on this story for this afternoon’s edition. The Tribune is in competition with the morning paper, the Tulsa World, and if we don’t get an advance lead, we’ll get beat. By your press conference time tomorrow, our paper will have gone to bed. I don’t want to read about it in the World the next morning.”

There were a few moments of numb silence on the phone line. Scott was weighing the old adage, “One in the palm is better than two birds in the brush.”

Finally, he conceded to “leak enough details” for an advance story that afternoon in the Tribune, but not reveal all the plans for the All-American, on one condition.

“What’s that?” I asked. Scott said, “Come to the press conference anyway tomorrow.”

“Sure, it’s a deal,” I quickly agreed, trying to get off the phone to make the final home press deadline. The six-column-inch story played out in a box item on the Tribune’s front page of the sports section.

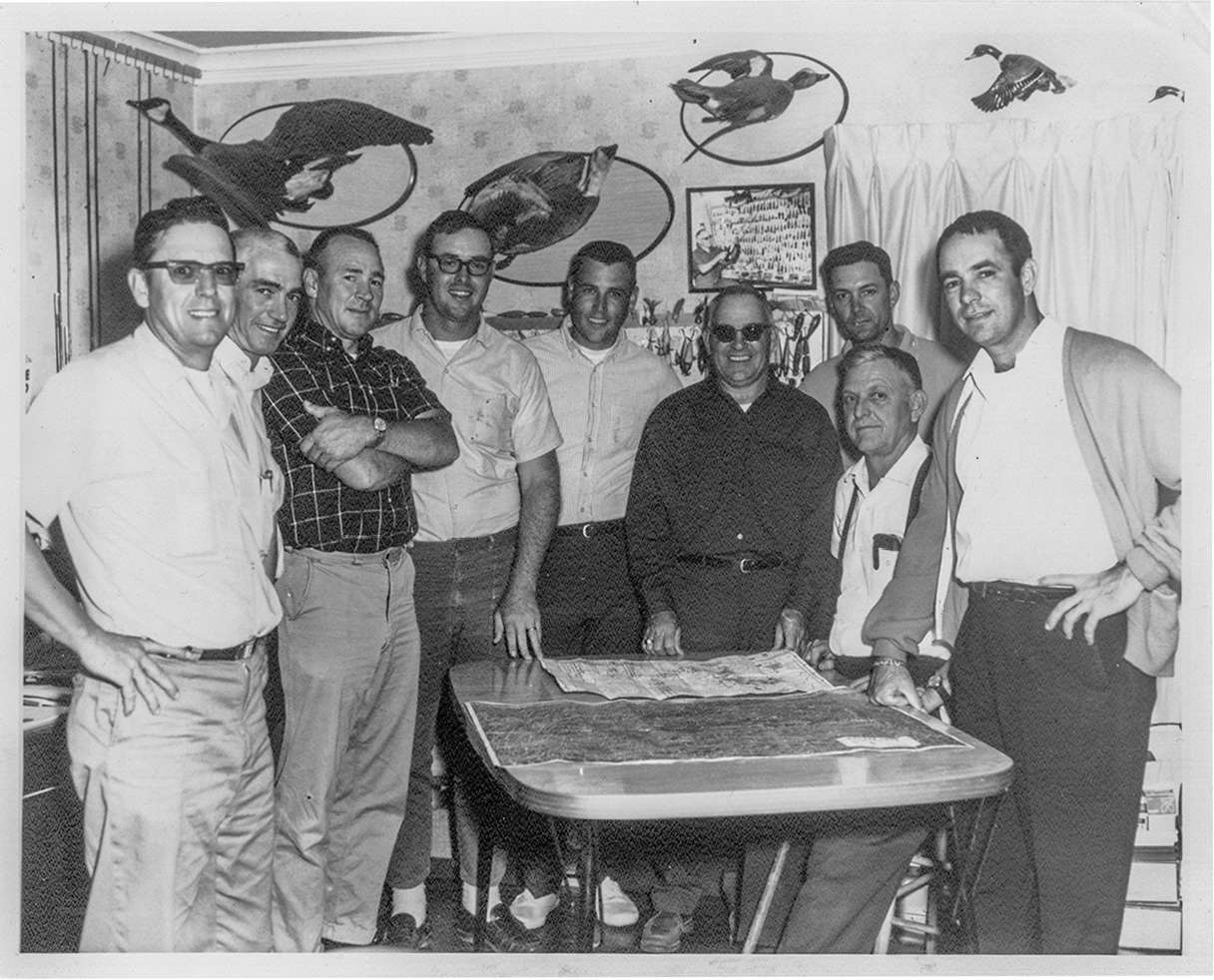

The press conference audience mostly consisted of Springdale chamber officials, a few Beaver Lake dock operators, banquet hotel waiters and a few curious outdoor writers, like John Fleming of the Arkansas Gazette from Little Rock, Floy Scroggins of the Beaver Lake News and Smoky Dacus, a fishing reporter from a nearby Rogers AM radio station.

As Scott later said, “Everybody listened, ate their roast beef, belched and left after only a few follow-up questions.”

He continued, “There was one fellow at the back of the room, holding a coffee cup in his reel hand, and between sips, making notes on a Big Chief tablet.”

Scott recalls, “Walking to the back of the room, I introduced myself and was face-to-face with Bob Cobb, the outdoor editor of the Tulsa Tribune. He would proceed to pick my brain and pick apart my tournament concept as clean as a Salvation Army Thanksgiving turkey.”

My impression of Scott before we met head on was somewhat unfavorable. His sales pitch was a bit too slick and polished — the mark of an insurance peddler, not so much as a slick con man or promoter. As Scott explained later,

“There’s a marked difference between a promoter and a con man. A con man will only trick you one time. A good promoter will sell you again and again.”

Scott looked me in the eye and told me about his dream to make bass fishing more popular, to create bass angling heroes, to get the sport on TV and have fishing fans watch and learn how-to techniques — the secrets of bass angling pros — and how he wanted to create a “Take a Kid Fishing” movement and youth angling program, to ensure the future of the bass fishing sport.

One key to being a good promoter or salesman is the ability to prospect, identify and prioritize a sales lead. “In the insurance business, quality names [prospects] are 24-karat gold and need to be handled with utmost attention,” Scott said of his method for recruiting entries for his All-American Invitational.

Scott invested $1,250 of Applegate’s check in a wide area telephone service line and started cold-calling marinas, boat docks, bait shops and tackle shops, “dialing for anglers’ names.” A Montgomery contact, Charlie Bamburg, had handed Scott a business card from the Lunker Lodge, a noted fishing camp on Lake Seminole near Bainbridge, Ga. Answering Scott’s phone call was the lodge owner/operator, Jack Wingate. After a short introduction on his upcoming All-American Tournament, Scott got down to business and asked Wingate for the names of “serious bass fishermen.”

Wingate, in his slow, south-Georgia drawl, responded with, “Well, let me see here, Mr. Scott. I’ll get my customer log book. Can you hang on?”

As fast as Scott could write the names, hometowns and maybe phone numbers, Wingate reeled off the lineup — including names like Billy Burns, a Kentucky tobacco farmer, who Circle claimed to be unbeatable with his jig and eel fishin’. Stan Sloan, a Nashville, Tenn., correctional officer, who kept the road hot to Seminole in the spawning season. Later, Sloan would take the bass fishing world by storm with the introduction of his long-armed Zorro Aggravator spinnerbait.

From the Wingate conversation, Scott gained a half-dozen tournament entries, including Wingate, who wanted to test his bassin’ skills against the “world’s best bass fishing talent.”

Scott’s goal was to register l00 fishermen for the All-American, but entries from the Tulsa, Okla., area were only a trickle, despite the T-Town city limits being only 100 some odd miles from Beaver’s shoreline.

The phone rang on the Tribune’s sports desk, and to my surprise, I heard Scott’s voice: “Bob, I need some help trying to get Tulsa-area anglers interested to enter the All-American tournament.

“I’ve got an idea up my sleeve, if you’ll get the ball rolling,” Scott said.

“OK, what’s my play?” I asked.

Scott cleared his throat for effect and said, “I understand some Tulsa bass boys think they’re pretty good — maybe better than most on catching bass on Beaver. I’ve got a guy from Memphis Bass Club that swears his guys can whip any team the Tulsa crowd can get together to fish the tournament.”

Scott went on to explain, “He’s been bragging around the docks how the Memphis crew can beat any and all comers. He claims, head to head, Tulsa’s anglers can’t compete — been calling the T-Town fishermen a ‘bunch of perch-jerkers.’”

Here the plot thickens. Scott’s voice dropped to a whisper, as if planning a military sneak attack. “You will get a letter, a challenge, from Clyde A. Harbin of Memphis as an open letter to Tulsa anglers, to throw down the gauntlet. Hopefully, Harbin’s intimidating tone will rile up some Tulsans to take the bait,” confessed Scott.

“Sounds like an open invitation to defend your bassin’ manhood. Should stir up some folks hereabouts. Mail the letter. We’ll write a column and poke the beast.”

The Tribune’s weekly outdoor page published on Thursday afternoon with the following “Outdoor Notebook” column lead-in:

HELP WANTED — Ten to fifteen of the roughest, toughest, two-fisted black bass fishermen in Tulsa County for three days of hard fishing on Beaver Lake to put down a gang of Memphis, Tenn., bass dabblers who claim to be the world’s best bass anglers.

The column went on to underline my belief that “Tulsa spawns the wildest, best and most enthusiastic bunch of bass fishermen in captivity.”

Harbin, as captain of the Memphis Bassmen, was quoted as saying, “All I’ve heard around Beaver Lake is how that Tulsa bunch keeps the road hot coming over to Beaver and all the bass they catch. We don’t think another group can out-fish Memphis, even on their home waters.”

Also, an outspoken Memphis youngster, Bill Dance, piled on: “There will be some bass fishermen with good reputations that won’t enter because they’re scared they will get their names tarnished if they blank at the weigh-in.”

The next morning, the phone on the Tribune sports desk alerted me someone had swallowed the bait. Bill Harper looked my way and said, “A guy on the phone wants the outdoor writer. Seems a bit angry.”

“Hello. This is Bob Cobb. How can I help you?”

The voice announced, “This is Don T. Butler. I want to know [where] that bigmouth from Memphis gets his gall to slam Tulsa fishermen, and how can I get in that bass fishing tournament at Beaver?”

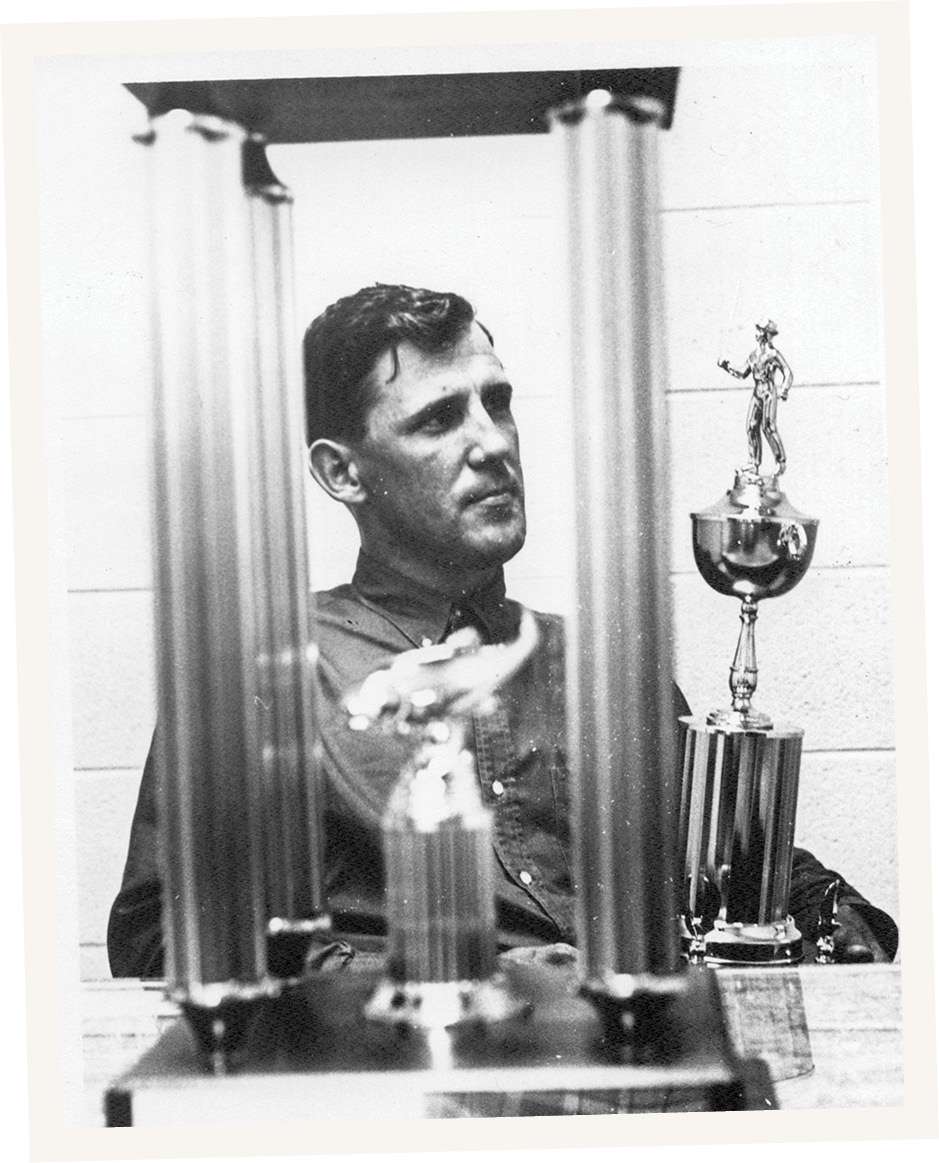

With those words, Butler engraved his name into the history of the bass fishing hall of fame. The Tulsa lumberman quickly built a coalition of fishing friends, organized the Tulsa Bass Club and delivered a 12-man team to accept the Memphis bass men’s challenge.

As they say in Oklahoma, Butler took the bull by the horns. He sounded the horn, and Tulsa anglers snapped to attention. Butler’s style merited it. He was a natural born leader, with Oklahoma native roots and a way about him you might call “cowboy cool.” He was raw boned and 6 feet, 2 inches tall. Butler was taken from the John Wayne mold. Normally soft-spoken, he was still the dude in the room you’d welcome at your back in an Okie knife and gun club.

Back in the 1960s, there was a country and western tune about things you sure don’t do: (1) step on my blue suede shoes, (2) tug on Superman’s cape and (3) call a bass fisherman a “perch jerker.” Butler was most upset about the latter slur.

Gordon Yetman, a sales rep for the Tulsa-based Zebco Fishing Tackle manufacturer, outfitted the Tulsa team with forest-green windbreakers with the emblem “Tulsa Bass Club.”

The Tribune got caught up in the challenge/war and proudly sponsored an entry, Wes Littlefield, a super-stud among area bass chasers. Butler’s rallying call recruited several future stars in the bass fishing game, like Roy Self, a local publisher; Johnny Reed, a Northeastern A&M college student, who had scored well in Peskin’s World Series events; and future lure designer Jerry Rhoton, who made his nickname — Lil’ Tubby — into a fish-catching crankbait with a solid plastic body and a replaceable soft plastic wiggle tail.

Harbin had good reason to boast about the Memphis team’s bassin’ feats. The All-American tournament would introduce the likes of Bill Dance, a furniture salesman who would rise to TV fame as “America’s Most Popular Fisherman”; Charles Spence, who founded Strike King Lures; Carl Dyess, an overlooked angler of great skills who reportedly was Dance’s early days mentor in plastic worm fishing; and Gerald Blanchard, a future champion on the Bassmaster Tournament Trail.

Memphis and Tulsa would fish a tournament within the tournament. The total weight of each angler would count over the three rounds of competition. The team with the most poundage (points) would earn the pleasure of selecting a lure of its choice from the defeated team’s tackleboxes.

If this outcome might be compared to a battlefield surrender, it would rank alongside Robert E. Lee turning over his sword to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to end the Civil War. As it played out, the two sides went at it hook, line and serious.

After two rounds, the Tulsans had a slight edge in the total of their Top 10 lineup. However, as sports fans know, it ain’t over until the large lady is handed the microphone. And, Lady Luck is a fickle finger of fishing faith. She can turn on a missed fish, a broken line or the often-repeated excuse: “We just ran out of fish.”

The Memphis bass men ended up picking the cherries out of the Tulsans’ lure boxes. Maybe it was the fact that Memphis really did field the better bassin’ team. Or, just maybe the T-Town crew had a few too many brews, celebrating their two-day lead into the late hours before the early morning takeoff.

The Tulsans had two solid patterns working from the start: crankbaits on rocky, secondary points and Texas rigged purple worms on stumps off the creek channels. The final day of competition, they had to switch to the “Hangover Pattern.” Butler, to his credit, urged his team to hang tough, to rally, to play hurt. His “win one for the Gipper” speech had sobering guidelines: “Tie on a spinnerbait. Hunker in the bottom of the boat if you’re dizzy. Make a cast, and hope to get it wet.”

To the last cast of the day, these Tulsa Bass Club members were good at their sport and dedicated to sharing their “family fishin’ secrets” with a complete stranger. They provided the Tribune’s “Outdoor Report” with timely tips on hot area lakes and lure selections, and they offered the opportunity to tag along and share with readers their hard-learned winning ways. They were all good anglers and good guys — the partner you’d hope to draw in a tournament. Joe Dunham, Bill Cottner, “Fast” Johnny Reed, Dr. Bill Miller, Vern Pittman of Pitt’s Jigs, Gordon Yetman, Wes Littlefield and Don Greer served as the foundation on which the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society would be built.