Brandon Palaniuk has stated that if he were limited to a single type of sonar, he would choose 360 Imaging. His 360 Imaging transducer is fixed to the shaft of his Minn Kota Ultrex foot control trolling motor. One of the two Humminbird Solix 12 graphs on his boat’s bow displays only what the 360 transducer sees.

How it works

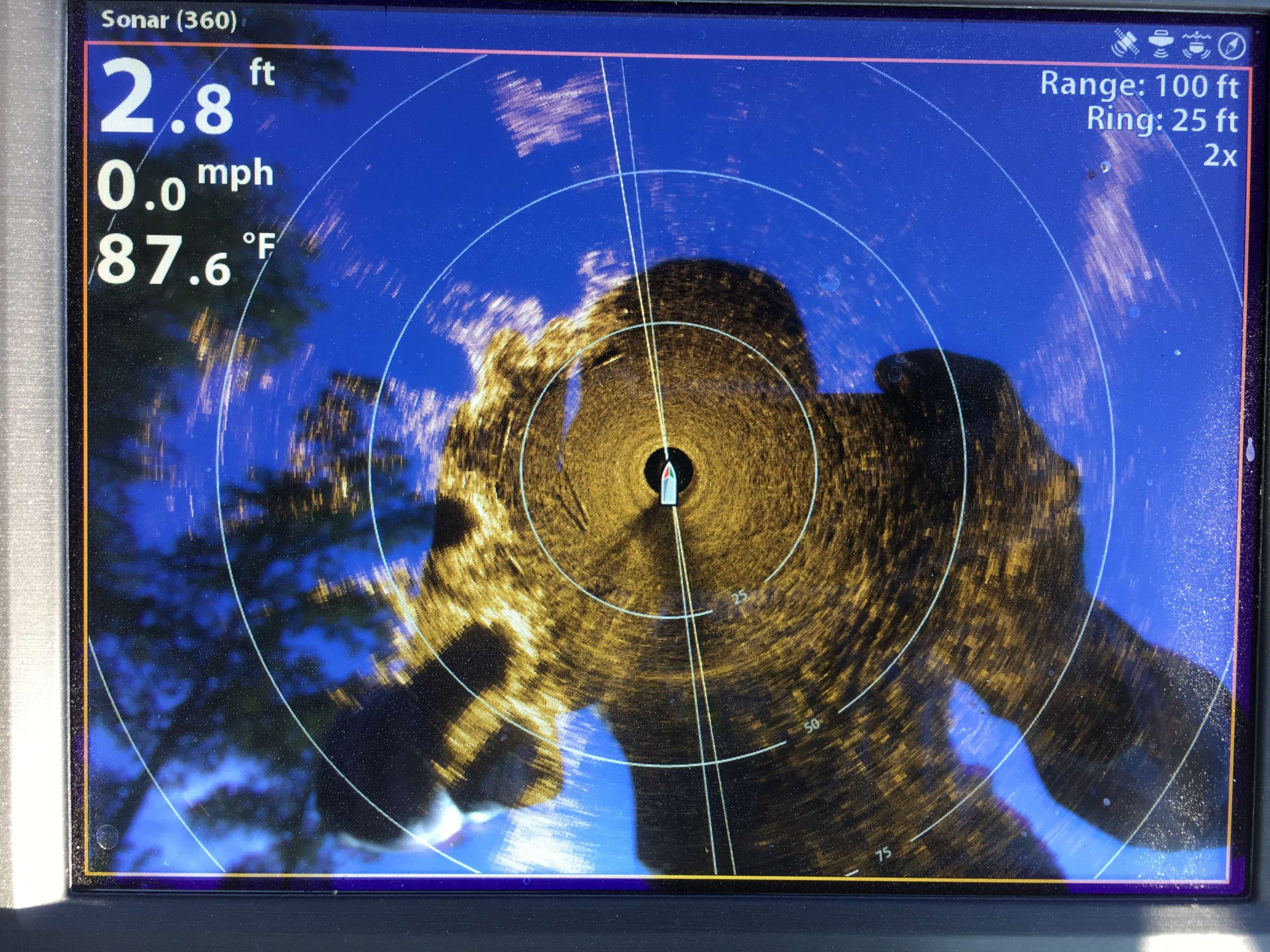

The display with 360 Imaging, which works with many Humminbird graphs, is similar to that of Side Imaging. The difference is that 360 reveals the bottom around your boat in a circle that may be set to a maximum radius of 150 feet.

The image is refreshed every few seconds with a diagonal beam reminiscent of the sonar devices you see in old war movies that feature a submarine. The 360 display is most effective when the boat is moving very slowly, as when fishing, or sitting still. Since the transducer does not move when you turn the trolling motor, the image stays constant.

360 imaging advantages

The most beneficial 360 advantage for Palaniuk is that it lets him find bass cover under the surface while fishing, which he does routinely.

“I can fish the bank behind other anglers and cast to cover they miss because it’s hidden under the water,” Palaniuk said.

With 360 Imaging, Palaniuk can see where cover or structure is in relation to his boat and cast to it before he gets too close to alert any bass that may be there.

Circular distance rings on the 360’s display tell Palaniuk how far he is from the target. This helps him put his first cast on the money and eliminate errant casts.

When casting to a small target, such as an individual stump, Palaniuk holds his rod horizontally above the screen and angles it so it lies over the boat icon in the middle of the circle and the target. This points his rod directly at the object so he knows precisely where to cast.

Seeing is believing

I saw firsthand how Palaniuk routinely reaps bonus bass with the help of 360 Imaging after the 2018 Bassmaster Elite Series tournament at Chesapeake Bay was cancelled. We launched his boat at a Delaware impoundment he had never seen before. It looked to be about 200 acres and there were few places deeper than 6 feet. The shoreline had an abundance of laydowns, overhanging branches and stretches of bank lined with rushes rooted in inches of water.

Over the next few hours, Palaniuk dissected the bank cover with buzzbaits, spinnerbaits, jigs, shallow cranks and soft plastics baits. He never got a sniff. Throughout this time, he kept an eye on the 360 display.

As Palaniuk worked the bank into a wide pocket, the 360 revealed a blown-out bridge well away from the shoreline.

There was no indication on the bank, the water’s surface or on the chart map that the bridge existed, but it was starkly evident on the graph’s display. The water was only 5 or 6 feet deep in the creek channel that had once been under the bridge.

360 payoff

Palaniuk began casting to the bridge with a shaky head worm and soon hooked a heavy fish. He worked it to the side of the boat when the 5-pound-class bass exploded out of the water and threw the bait.

Palaniuk soon hooked another bass from the bridge with a drop shot rig. This one broke his line. He hooked a third and final bass from the bridge with a drop shot rig and landed it, a 2-pounder. Although he never coaxed another bass from the bridge that day, all three of those fish were bites he would not have gotten without 360 Imaging.

Awhile later, Palaniuk was again fishing shoreline cover when he cast a squarebill crankbait ahead of the boat well off the bank. He set the hook and promptly landed another 2-pounder.

“That bass hit right on the edge where a hard bottom met a soft bottom,” Palaniuk said.

I told him he was joking. The boat was floating in 3 feet of water over what appeared to be a flat, featureless mud bottom. The idea of having a hard bottom transition in such a place seemed outlandish.

“No, really,” Palaniuk said. “Come up here and look.”

I moved up to the bow and peered at the 360 display. Sure enough, it showed a bright, hard-bottom point beneath the surface. The change in depth from the hard to soft bottom must have been mere inches. Here was another bass

Palaniuk would not have caught without 360 sonar. In fact, the four bites Palaniuk got thanks to 360 Imaging were his only bites that day.

Manual 360 settings

In most instances, Palaniuk sets the display to show only the front half of the circle so he can see what’s ahead of the boat and off to either side. This also enlarges any objects on the display, which makes them easier to interpret.

He usually sets the distance radius at 115 feet, although he will drop down to 100 feet in extremely shallow water and out as far as 150 feet in water 30 feet deep or more.

“I like the brown color pallet,” Palaniuk said. “It does a better job of contrasting the image.”

After he had fished the blown out bridge, Palaniuk anchored the boat with his Talons so I could look at the bridge on 360 Imaging. He scrolled through all the color pallets. I could see the bridge with any color, but had to agree that the brown pallet revealed the most detail.

Palaniuk also manually increases the sensitivity and sharpness. He sets both from 13 to 15 depending on the bottom makeup.

“A softer bottom requires higher sensitivity and contrast than a hard bottom,” he said.