Ray Scott had a lot of visions when he started B.A.S.S. The well-known story begins with him sitting in a motel room in his underwear, watching basketball and envisioning people as excited to see professional anglers catch fish as men in shorts shooting at baskets.

The “brainstorm in a rainstorm,” as Scott referred to it, was the beginning of everything that is celebrated in these pages. It’s easy to get lost in the visions of grandeur, even with a backdrop that includes a grown man in his underwear.

The truth is, before the screaming fans, packed arenas and a litany of fishing heroes, Scott knew all those visions would never happen without the presence of a specific foundation that is always there but seldom thought about.

“Ray had a lot of dreams,” said Bob Cobb, who walked in lockstep with Scott while helping him see those dreams come true. “He knew for any of it to work, he had to have strict rules and absolutely no monkey business.”

The “no monkey business” mantra was ingrained into the fiber of the sport before Scott ever put his pants on in that motel room. He worked up a set of rules, written on the brown paper of a Kroger grocery sack, keeping in mind that every rule was designed to level the playing field. Rules were included that kept anglers from the same state from fishing together to offset the monkey business potential.

Fresh on his mind was a team tournament from another organization in Oklahoma in the years before B.A.S.S. An angler practicing for the event on Grand Lake found a basket tied up with bass inside. He notified Oklahoma Wildlife Federation officials. They marked the fish by cutting the dorsal fins and had wildlife officers surveilling at the scales.

When the fish showed up, the anglers thought they were going to win. But the OWF officials confronted them, showed them their proof and gave them a 30-minute head start before they told the crowd about their cheating ways.

Cheating had been averted, but just the thought someone would try it haunted Scott.

In his biography Bass Boss, Scott detailed an early story of “The Cheater.” It centered on a contestant who had mentioned to his partners in the first two days of the event that he “had an ace in the hole” if they didn’t catch anything. Same for the last day, when he fished with Bob Martin. On that final day, “The Cheater” visited a wire basket and pulled out a handful of fish to weigh in.

Martin insisted over and over that he throw back the fish. But the man refused. At the weigh-in, Martin made the Bassmaster Classic and signed the man’s weigh-in slip, knowing that it was false but wanting to just get past it. Days later, that whole “ace in the hole” comment landed on Scott’s ears and the story came out. The cheater was banned from Bassmaster events for life, and Martin, for keeping his mouth shut, was taken out of the Classic and suspended from competition for a year.

After that, any hint of impropriety was reported — including one of the more comical attempts, known as the “Guppy Man Caper.”

The backdrop was Buggs Island, and the Guppy Man showed up to the takeoff wearing a full-length raincoat even though there were no clouds in the sky. Out on the water and paired with Connie Baker, the Guppy Man from the back of the boat would occasionally say, “There’s a good one,” and by the time Baker would turn, a fish would be dropped into the livewell.

There were no splashes, fish jumps, grunts or any other clues. Baker took the Guppy Man to Harold Sharp after the third quiet fish fight, and it was revealed the man had a stringer of bass around his neck and hidden under his raincoat.

“That was the most — I don’t know how to describe it — ingenious or stupid thing to try and pull something like that,’’ said Cobb.

Through the course of these attempts, Scott’s resolve carried on to the rank and file, and even more so to the fans who wanted their heroes to be above reproach.

Fast forward to 2011, the Bassmaster Northern Open on Lake Erie. Nate Wellman, after watching his partner, Joe Stois, land a 4-pound fish, offered to buy it for $1,000. He repeated the offer a few times, including at the weigh-in.

Stois reported the exchange. Was it a joke or a serious attempt at circumventing the rules? Only Wellman knows, but he was fined either way. Bass fishing fans were so incensed, their outcry so loud, it forced his banishment from other events.

The idea that the rules are important had become ingrained in the sport.

“The thing that Ray did that can’t be understated was he gave all of us a respect for the sport by making sure the rules were unquestionable,” said George Cochran in an interview days after Scott’s passing in 2022. “Ray liked to joke and have fun. But when it came to the rules, they were the bible we all lived by, with no exceptions. You could joke about anything with him, but not the rules.”

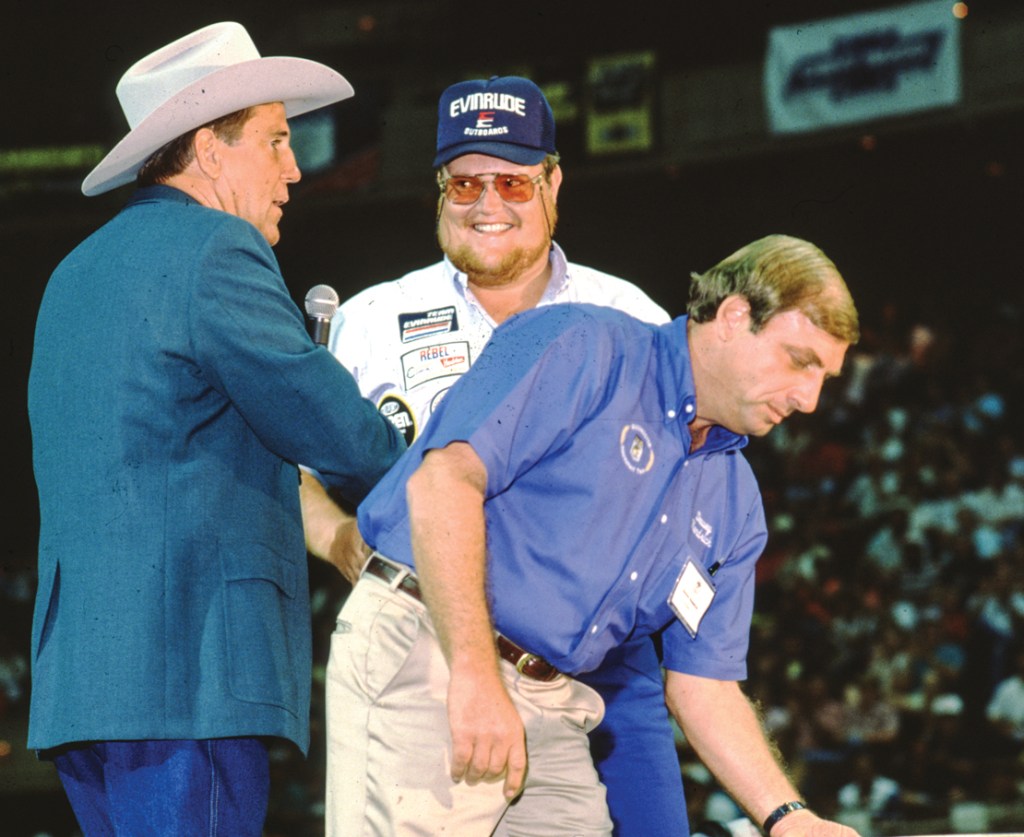

In the middle of Scott’s day-to-day business of building B.A.S.S., hawking the wares of individual anglers like a carnival barker espousing their honor and respect, he never balked at the opportunity to preach the gospel of strict rules and passing on an unwavering viewpoint of doing what was right.

In one of those long-ago conversations, Scott would often pass on a story from the early days. The names of those involved have been forgotten, not omitted. The point of the story was how it solidified his resolve to have “no monkey business.”

It was one of the first events where Scott was using his magic to get everyone involved and on track to building the sport. It was after a first-day weigh-in, and Scott again was in his motel room, possibly in his underwear, when a knock came at the door.

Outside was a contingent of anglers from one of the Southern states — again, which one is forgotten, not omitted.

“One of their youngest anglers who was in the tournament had gotten stuck in the back of a creek and didn’t make it back in time for the weigh-in,’’ Scott said.

The unfortunate angler had caught an 18-pound stringer, which would have taken the lead in the event, and that contingent wanted Scott to weigh them and count them.

“They were very clear,’’ Scott remembered. “You do this or no one from our state will ever fish one of your events again.”

It was simultaneously a slap to the face, in regard to the rules, and a punch to the gut in regard to a man who was trying to build a dream and needed everyone’s support. To lose a whole state of supporters was horrifying.

“But losing the whole sport because of something like that was even more scary,’’ Scott said. “I told them, ‘The rules say you have to be on time,’ and shut the door.”

Scott admitted to worrying about the impacts of his decision. But he knew “dreams don’t come true the wrong way.”

From that point forward, Scott’s resolve was built into Harold Sharp, then Dewey Kendrick and then Trip Weldon, who recently passed them on to Chris Bowes and Lisa Talmadge.

In each one of those aforementioned careers, there have been times when decisions had to be made that tested them.

“I believe the two most sacred things in bass fishing are the rules and our scales,” Weldon said. “They both have to be solid as a rock, and we go to great lengths to make sure of that. Those were the things that Scott believed in and made sure the rest of us were disciples of.”

In today’s world, following that line has implications not available back then. That group of anglers at Scott’s door that night would all have a social media audience, as would the young angler, all of them clamoring for the tournament director to do what’s best for their chosen hero.

“Those things can’t play into a tournament director’s decision,” Weldon said. “When something happens and you have a field of a hundred people, but you’ve got one guy that’s overstepped the boundaries, I’m looking out for those 99 that stayed within the boundaries. That’s how I looked at it. I’m trying to do right by them, by the people who obeyed the rules. We want to level the playing field as best we can, and it’s the only way.”

The history of tournament fishing is littered with rules violations, to the point that many still believe there is always some level of cheating or bending of the spirit of the rules from one end of the country to the other. Throw in a viral scandal of weight stuffing in a walleye event and a similar one during a U.S. Open, along with a variety of other things from other organizations, and it all adds fuel to the fire.

The history of B.A.S.S., though, is littered with instances of times when rules violations have not been tolerated and tough decisions had to be made, no matter who that implicated. A short list includes a day at Santee Cooper when Weldon had to disqualify Kevin VanDam, Alton Jones and Randy Howell for practice violations; add disqualifications of Mike Iaconelli and Gerald Swindle during Bassmaster Classic competitions. All of them can be described as heroes of the sport, and the violations were potentially damning to their careers at the time.

“We can all make mistakes,” Bowes said. “But as tournament directors, our job is to not make a mistake when it comes to following the rules. They are the standard [by] which we are all judged. In almost every instance where we have had to make a hard decision, the result has produced some anger and gnashing of teeth on the front end that eventually produces a respect for fair competition by the time it’s over.

“We are the keeper of the rules, and we take that very seriously. Truthfully, we have to, not because there is a lot of rampant rule breaking, but because our anglers, believe it or not, want us to be as strict as possible. They demand adherence among themselves and push us to be the best we can possibly be.”

Back in the hotel room, sitting in his underwear and watching basketball, Scott built his dream. The fulfillment of that dream, with the heroes doing it the right way, was as much a part of the vision as the screaming fans it has created.