The big talk this week at the 2020 AFTCO Bassmaster Elite at St. Johns River has been about the lack of eelgrass.

The fishing has been very tough this visit, considering the previous years kicked out very impressive five-bass limits of largemouth bass. And really, the lower weights this time around can be blamed on the weather. A large, blustery cold front hit early in the week, dropped water temps and pushed a lot of water out of areas that generally hold the highest concentrations of prespawn and spawning bass.

Blame the weather.

But the lack of eelgrass has been a hot topic for the past two years. Where has it all gone? What’s to blame? And will it come back?

To help sort this out, Trevor Knight, the Northeast Region Fisheries Administrator for the FWC has some interesting theories that certainly contribute to the situation.

“First off, the continued absence of the eel grass can be directly pointed at hurricanes the past two years,” Knight said. “Hurricanes Michael in 2018 and Irma in 2017 certainly had major impacts on Florida fisheries. The wind alone is largely responsible for destroying countless acres of vegetation. It just takes time for aquatic plants like eelgrass to recover, and they require certain conditions to be reestablish.”

Knight said the eelgrass is essential to successful black bass spawning and recruitment because it provides adequate cover for the fry and young-of-the-year.

“There are large populations of predator fish in Florida waters, especially gar and dogfish in the St. Johns River and Lake George,” he said. “They will target and feed heavily upon whatever is most abundant. In some cases that might mean black bass. With the lack of eelgrass over the past couple of years, overall bass recruitment is down. That doesn’t mean there aren’t still plenty of bass — and big bass — to catch, it just means recent year classes are lower.”

Juvenile bass depend on quality cover to act as a nursery so they can survive predation from birds and other predator fish. But, like many circumstances in nature, this situation is cyclical. The eelgrass will bounce back. But what else is slowing its recovery?

Knight said that not one specific factor is the sole cause, it’s a combination of multiple factors.

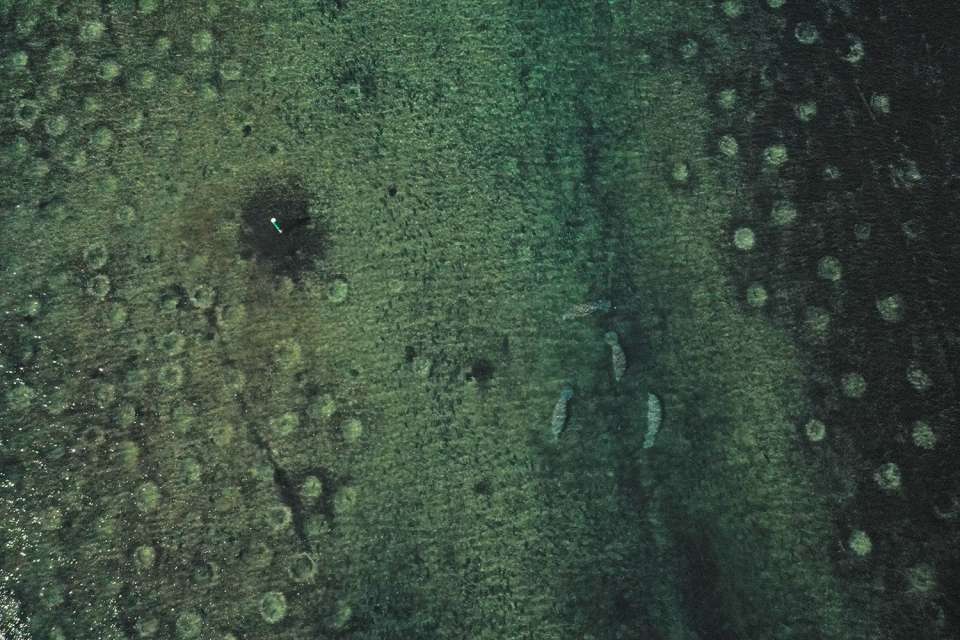

Two species of invasive fish have been linked to eelgrass habitat damage.

“The armored catfish and the tilapia are two aggressive spawners, they literally take over the structural elements on which they spawn,” he said. “That means grass won’t grow there. The tilapia attempt to spawn all year long, making them very prolific.

“We also haven’t had much cold weather over the past couple years. A two- to three-week stretch of freezing temps would kill a good number of the tilapia and armored catfish. A reduced population of each invasive would encourage more eel grass growth in certain areas.

“Another factor is the continuous wet weather we’ve been experiencing over the past two years,” he continued. “The water levels in the river and on Lake George has been higher than normal, which makes it hard for the eelgrass to germinate and begin growing. Generally, it grows best in 1 to 2 feet of water on firm sandy bottoms, sometimes mud, but not a soft murky substraight. Average water levels have exceeded that mark recently.”

Interestingly, eel grass will grow in deeper water, but usually only after shallow eelgrass is well established. The existing grass will filter the water, clear up the surrounding water thus allowing more sunlight penetration, which encourages more grass to grow in deeper water.

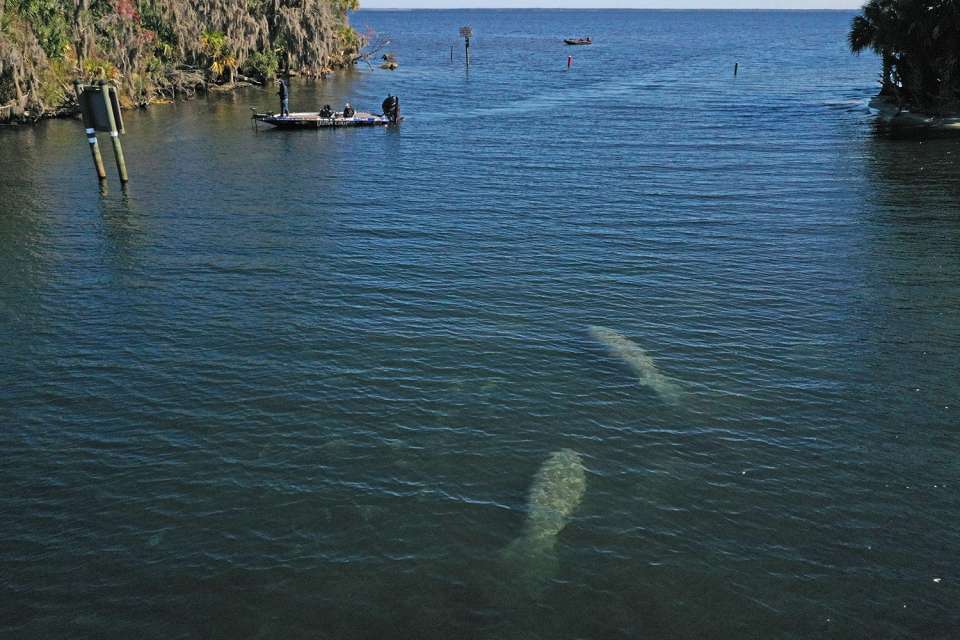

The other factor that should be considered is how much eel grass is consumed by the wintering manatees. Yes, they are a national treasure and a protected animal, but they are very large critters and require an impressive daily caloric intake to sustain themselves.

If you were to search Google you’d find some interesting stats.

A single 1,000-pound sea cow will spend about seven hours each day foraging or grazing 7% to 15% of their own body weight in food. That roughly works out to about 150 pounds of food per day. They mostly eat grass and other aquatic vegetation. Therefore, the manatees are grazing off the eel grass before it can become fully established.

This is not to imply that these giant sea creatures are a problem, not at all. But they are a contributing factor to the absence of eel grass in Lake George and along the St. Johns River. The more you know …

Knight believes that a year of drought followed by a relatively dry year will bring the eelgrass back in strong fashion.

“Lakes across the entire country go through cycles,” he said. “And this situation is no different. It wouldn’t surprise me at all to see the eelgrass reestablished to normal levels in as little as two years if the conditions cooperate. But that’s impossible to forecast. I’m confident it will come back, though. It’s just a matter of time.”

The more eelgrass that grows, the clearer the water gets, which makes it easier to see and catch bass.