Her name was listed as “Mrs. M.W. Taylor,” and if it seems chauvinistic, it was … but it was a different time — a time when women had all the rights but little identity, especially when it came to activities dominated by husbands, fathers and brothers. Mrs. Taylor was listed in the Idaho state fishing records where she held the top mark for largemouth bass for generations. In fact, in late 2023, no one knew how long she had held the record. No date was listed for her catch.

There was also no length or girth, no information about the lure or bait used, no photo. Just a name, a location — Anderson Lake —and the weight: 10.94 pounds. It wasn’t a lot to go on, but that’s what intrigued me about the record.

I figured “Mrs. M.W. Taylor” to be a likely candidate for expungement. With so little information and a catch so old it was undated and unphotographed, it seemed destined for the scrap heap, just another tall tale without substantiation. I’d probably recommend that state authorities replace it with something more concrete, more supportable … more recent. There’s a largemouth bass state record in 49 of the 50 states — all but Alaska — but none offered less information than the Idaho record.

As with any bass fishing cold case, I start with the information I believe I can rely on. I soon learned there’s more than one Anderson Lake in Idaho, but the one that produced the state record is near Harrison in Kootenai County, just off the Coeur d’Alene River. It covers 720 acres and is part of a chain of lakes.

Of course, it was harder to find the angler. Women were often identified by their husband’s names through the first half of the 20th century. But I cringed that the surname was so common, and the rest was only initials. It was a modest starting point, but a productive one. While searching for references to giant Idaho bass, I found a 1949 story in The Spokane Review (Spokane, Washington) about a 9-pound, 14-ounce largemouth bass. The reporter called it the biggest in the previous decade from the “Inland Empire,” which I learned is eastern Washington and northern Idaho.

The reporter was wrong. A bigger bass had been caught, and who do you think wrote to set him straight? It was Mrs. M.W. Taylor herself. Here’s how he reported it:

“Mrs. M.W. Taylor, E4038 Fourth Avenue, reports she landed a large mouth last October in Anderson Lake, Idaho, that scaled 10 pounds, 15 ounces. Anderson Lake is near Harrison, and “the bass there will either take a water dog or plug any time,” Mrs. Taylor says.”

Suddenly I had a month, a year, confirmation of the lake, a residence address and some obvious passion from the angler herself. Mrs. Taylor was not just a real person, but she referenced the weight of her record fish and even shared some angling advice.

I expanded my search to Washington State — particularly Spokane — and I found Mrs. Taylor’s husband (after all, his was the only name I had). I learned that M.W. Taylor was a successful, and colorful, Spokane dentist who loved fishing and hunting.

Maurice Winfred Taylor was born in Missouri in 1881. Once I found him, it was easy to find his wife, our angler — “Mrs. M.W. Taylor.”

Her maiden name was Mary Alice Hurt, and she was born in 1885 in Keytesville, Mo., the fifth of eight children. She married Dr. Taylor in 1901, when he was 19 years old and she was 16. Eight years later, she gave birth to a daughter, Martha Lee.

The Taylors moved to Spokane sometime between 1920 and 1922. Once there, they started to show up in the newspapers. Mary Alice was a pillar in the society pages, but Dr. Taylor was a lightning rod of drama, much of it surrounding his interest in the outdoors.

The doctor was cited or arrested for illegal possession of gamebirds, exceeding the hunting bag limit, violating an anti-noise statute (his geese and dogs regularly disturbed the neighborhood), hunting without a license, hunting ducks out of season, trespassing on a migratory bird reserve and more. Most of the charges were dismissed — the local authorities seem to have had an axe to grind with him — but plenty stuck. He paid a small fortune in fines over the years.

Mary Alice was a socialite. The papers reported on her poetry readings, committee appointments, dining engagements and her exemplary performance on the “rigorous birthday card committee.”

The Taylors lived good and largely uneventful lives until 1928. That’s when Mrs. Taylor’s brother — Claude Hurt, a bank president in Mobile, Ala. — was killed in an attempted robbery. The man who pulled the trigger was executed. His accomplice got a life sentence.

Eight years later, the accomplice escaped from prison and went to Philadelphia, where he began a new life, got married, had children, started a business, made friends, was active in church and generally was on the straight and narrow before being recaptured in 1947. Many people from his new life came to his defense, including Mrs. Taylor and her two living sisters. They asked that the accomplice be released to go back to his family rather than serve out the rest of his sentence.

Her advocacy was national news. Here’s a quote that was published in several newspapers in October 1947:

“If the man is trying to live a good life and do right, I would be glad to have him set free. I suppose the people who live near him would know more about it, but since he has a wife and a family, I think it would be alright to set him free.”

He was released the next month.

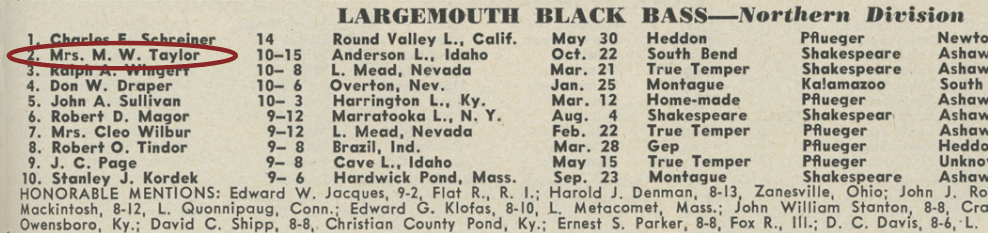

Less than a year later, on Oct. 22, 1948, Mary Alice caught a 10-pound, 15-ounce largemouth bass — the Idaho state record. She was 63 years old and using a South Bend rod, Shakespeare reel, Ashaway line and a Pflueger Pal-O-Mine lure. The catch earned second-place honors for Largemouth Black Bass in the Northern Division of the annual Field & Stream Fishing Contest.

Was it a lucky cast? Maybe. All record catches are lucky to some degree, but four years before her state-record catch, she finished sixth in the Field & Stream contest with a 9-pound, 11-ounce largemouth from the same lake. That’s more than luck.

Mary Alice Hurt Taylor died in 1974, one day after her 89th birthday. She’s interred in Riverside Mausoleum in Riverside Memorial Park in Spokane.

Idaho Fish and Game has updated its records to include the information uncovered by this Cold Case, including Mrs. Taylor’s full name and the date of her catch.

A photo of the Hurt family accompanies this article. Mary Alice is in it, along with her parents and siblings. Unfortunately, I can’t positively identify her. That part of the mystery remains unsolved.

Originally appeared in Bassmaster Magazine 2025.