Across the country on bass lakes from California to Texas, Alabama to Virginia, and northward into Michigan and New York, bass fishermen have learned that some of the best places to catch autumn largemouth are in tributary creeks where the bass are following shad during their annual postsummer migration into the shallows. Armed with crankbaits, spinnerbaits and other reaction lures, anglers often enjoy some of the most dependable shallow-water fishing of the year.

It’s a lesson Keith Combs learned well on his home waters of Sam Rayburn and Toledo Bend, but as more fishermen crowded into his favorite creeks each September and October, the Bassmaster Elite Series pro began searching for alternative patterns those same creek fishermen were overlooking. Through years of tournament competition — Combs won the 2017 Bassmaster Angler of the Year Championship tournament on Mille Lacs Lake and is a three-time winner of the Toyota Texas Bass Classic — he has perfected enough secondary options that on some lakes, he doesn’t even go into the tributaries during the fall months. Here are three of his favorite autumn alternatives.

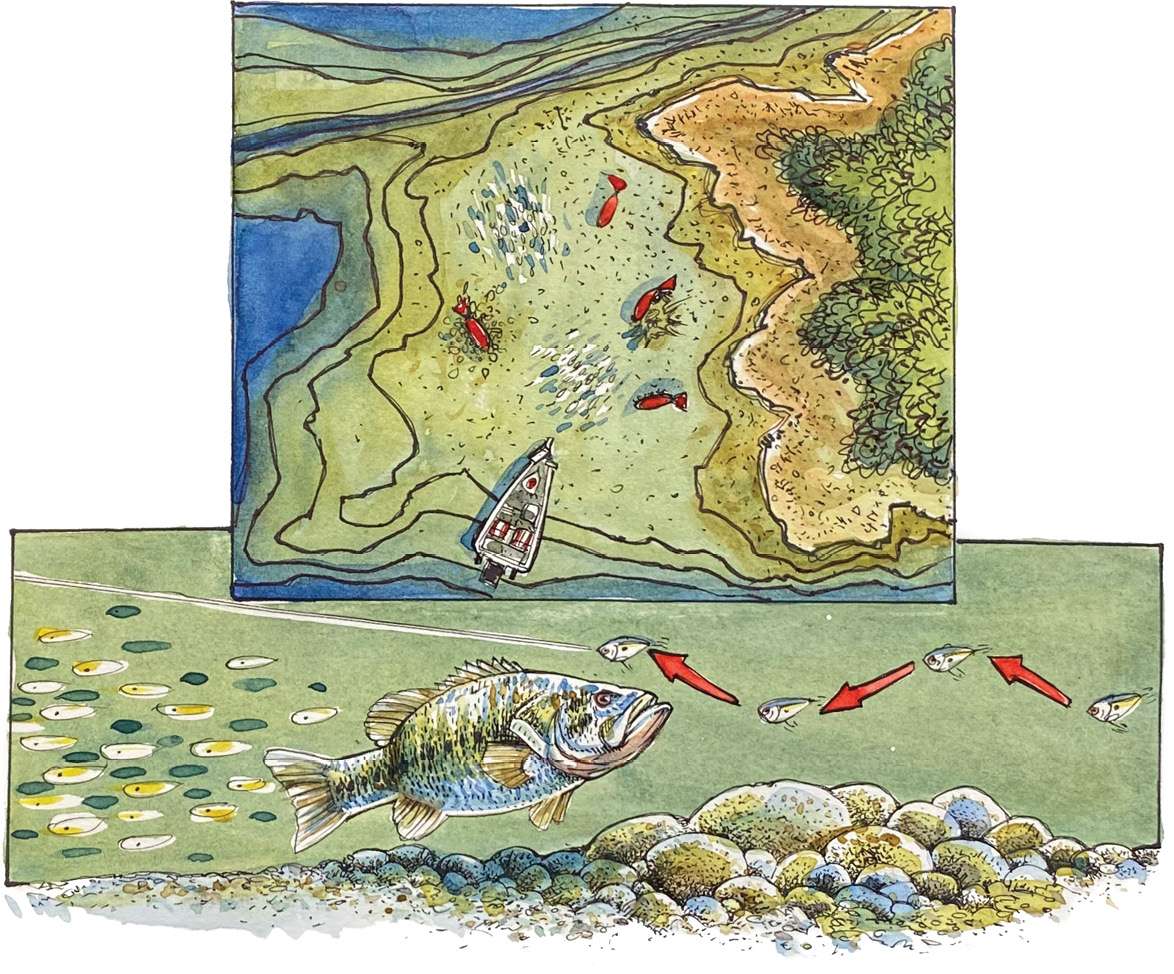

Main-lake flats

“As the late-summer patterns begin to go away in the deeper water, my favorite alternative is to move to the largest main-lake flats I can find, places like the 1215 Flats on Toledo Bend or the mouth of Harvey Creek on Sam Rayburn,” says Combs. “Every lake has places like these — large, featureless and fairly shallow flats.

“Often, these flats don’t have anything on them — no cover, no depressions, nothing to hold bass on them. But bass still use them. You’ll see the fish just cruising or perhaps chasing schools of big gizzard shad, but they’re not relating to any type of specific cover or structure.

“This is primarily a searching pattern, and all I try to do is cover as much water as I can. If I do find a stump or rockpile, it can be a plus, but even vegetation doesn’t seem to be that critical. When I’m fishing this way, I like to say I’m just wandering and casting everywhere.”

The lures Combs prefers for this type of fishing won’t come as a surprise: lipless crankbaits, soft jerkbaits and buzzbaits when he’s in extremely shallow water. He uses a fast retrieve because at this time of year, bass will chase a lure, and he includes some rod-tip action to make the lures act a little more erratic.

“You have to use a presentation that gets you noticed,” he continues, “but once you do find where the fish are, you can tone your retrieve down a little.”

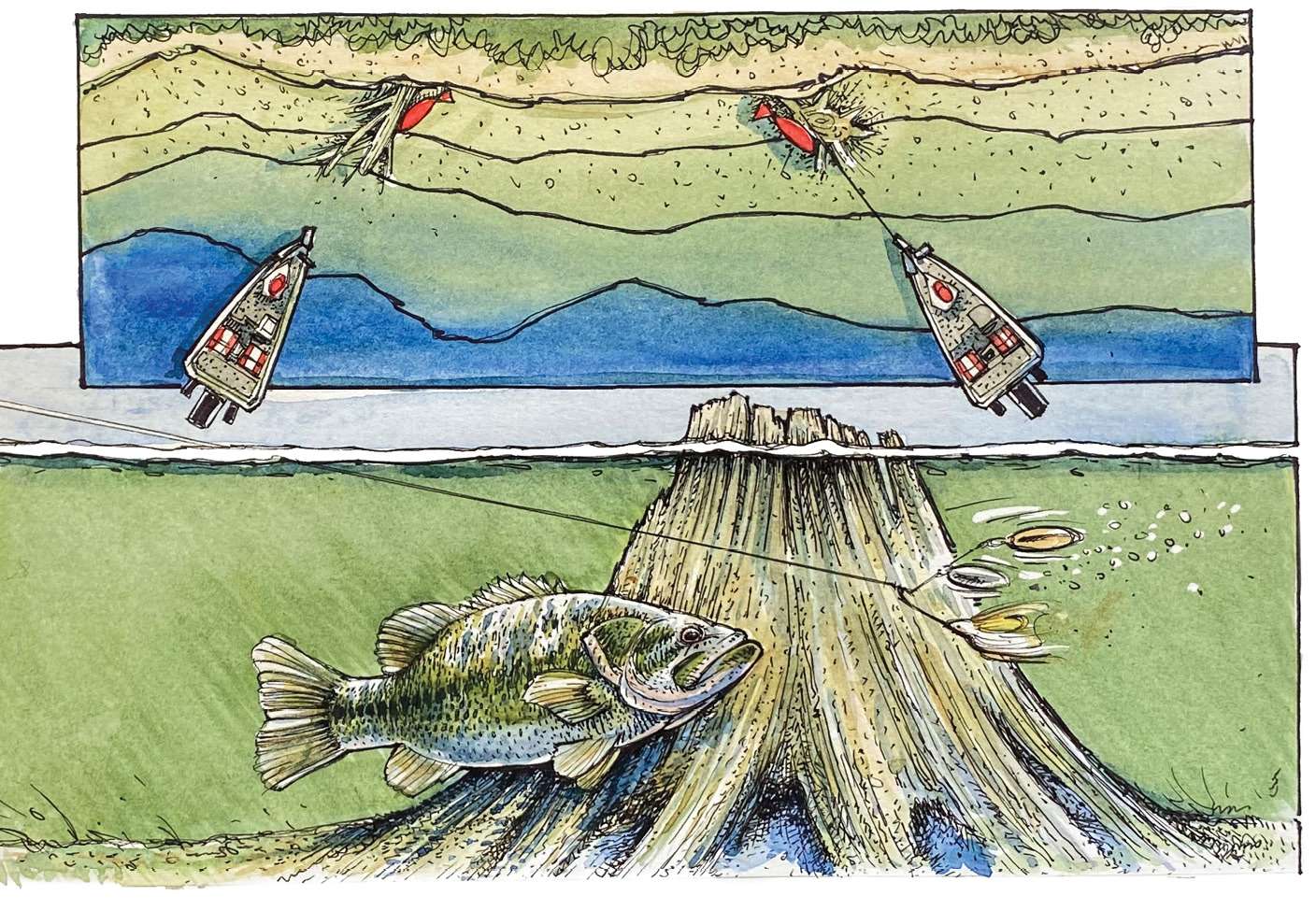

Isolated cover

“Fishing isolated cover is not so much a searching pattern as it is a one-fish pattern,” says Combs. “What I do is run down main-lake shorelines that look completely featureless — again, places other fishermen are prone to overlook. What I try to find is one stump, one laydown, maybe a fencerow or even a piece of floating driftwood in just 3 or 4 feet of water. It has to be isolated and by itself.

“On a big flat, you find little groups of fish, but on isolated cover like this, it will be one bass at a time. But, the beauty of this pattern is that you can return to these individual pieces of cover three or four times during the day because another bass will come in to take the place of the one you caught earlier.”

Texoma is famous for this pattern because of the stumps and rocks along the shorelines, and at Table Rock, Combs has fished isolated cover like this all over the lake. During a tournament at Clarks Hill, he dialed in this pattern on the second practice day and never made another cast until competition began two days later. He spent the remainder of his practice waypointing every piece of cover he found, then simply ran them during the tournament. He had the pattern all to himself and finished in the Top 10.

“Fish don’t live on any of this stuff,” he says. “They’re just traveling along and [stopping] at these places because they offer a little shade, security and maybe an easy meal. The more isolated the cover, the better the chances are a bass will use it.”

Spinnerbaits and jigs are Combs’ favorite lures for this pattern, and if neither of those draws a strike, he might try a shaky head rigged with a green pumpkin finesse worm. He doesn’t spend a lot of time on any single target. On a log or laydown, he may run the spinnerbait down each side once or twice, then throw the jig a couple of times and then leave. This might take three minutes, and he will leave feeling confident there isn’t a bass on it.

“You can’t usually fine-tune this pattern,” he says. “It’s a total junk deal, and it’s completely random, but at the same time, these pieces of isolated cover are definitely high-percentage spots. If I know the lake I’m fishing, I might hit 40 or even 50 separate places in a day because I know eventually, I’m going to catch bass.”

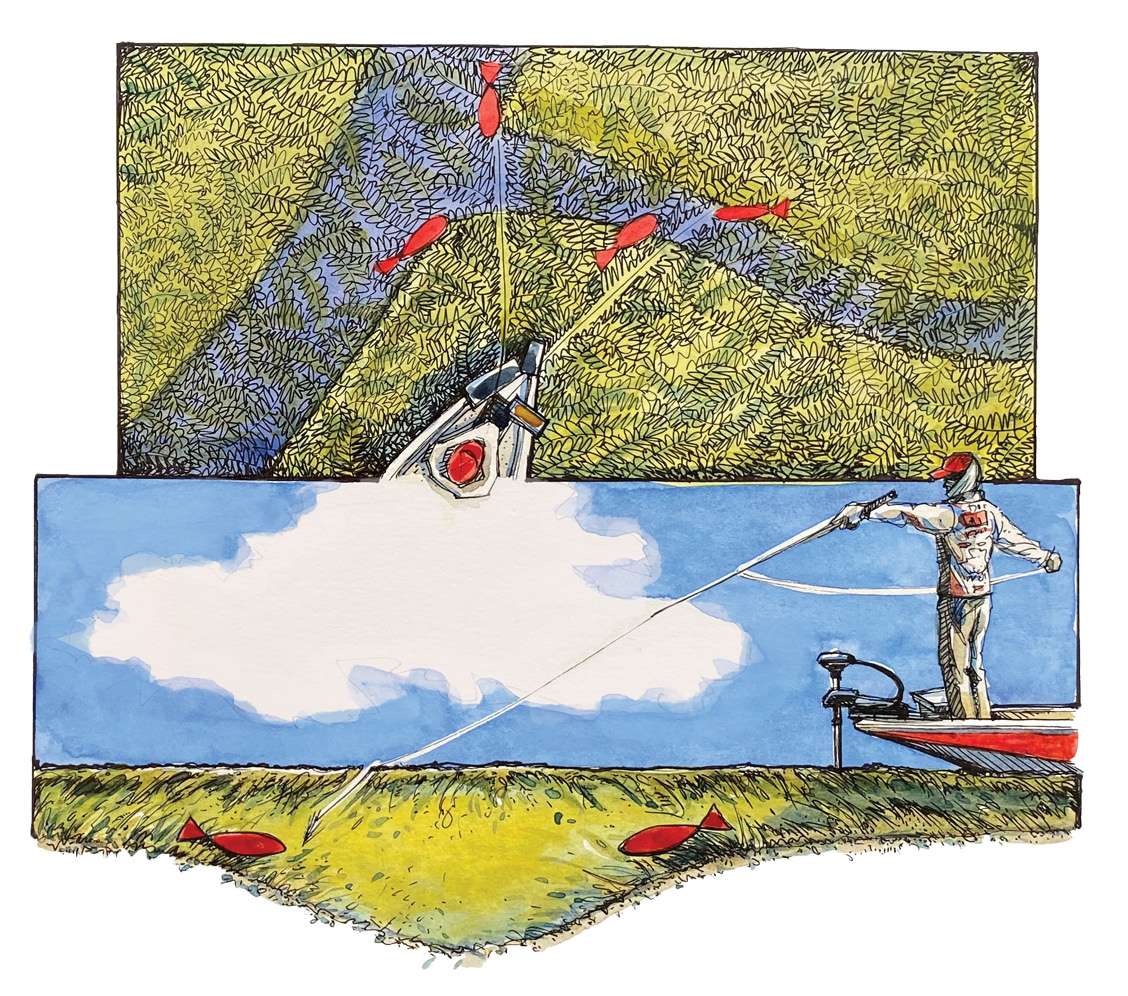

Small grass-covered ditches

“In this pattern, I’m not just casting randomly across the huge milfoil and hydrilla beds you might find on Guntersville, Toho or Rayburn,” emphasizes Combs. “Instead, I look for small, subtle ditches and drains under that grass. The best ones tend to be little ditches that run into larger ones, and often they’re tough to see from the surface.

“Good electronic mapping really helps with this pattern, and again, what I’m trying to do is fish places other anglers commonly overlook. These grassbeds have been there all summer and they’ve received a lot of fishing pressure, but the smaller ditches and side channels seldom get fished that hard. Very often, the vegetation simply forms a canopy over the ditch, and bass gather underneath that canopy.”

How Combs fishes these drainages depends on the depth of the grass. His two favorite presentations are to use a heavy 1- or 1 1/4-ounce jig in deeper vegetation and a floating frog over the top of shallower grass. He stays within about 10 feet of the edges of the ditches, pitching the jig out, letting it punch through into the open water below the canopy, then just hopping it once or twice off the bottom. In slightly deeper 6- to 8-foot depths, he fishes fast.

“I fish slower in the shallow water, working a frog steadily right across and down a drain,” he says. “Many times, I’m fishing the same places I’ve fished for years, but what the electronic mapping has shown is that the most productive grass areas often have some drain or slight depth change you can’t see from the surface. It may not be much, but generally speaking, the fish you catch on a frog on top of the grass are actually relating to some type of depression on the bottom.”

In this pattern, as well as when he’s looking for isolated cover or the large, featureless flats, Combs is staying on the main lake rather than joining the crowds in the tributaries. His patterns can exist throughout a lake, but diligent searching and fishing usually outlines a particular section of lake to be better than another.

Originally appeared in Bassmaster Magazine 2020.