The 1971 Bassmaster Classic at Lake Mead, Nevada, is remembered as the first world championship of bass fishing — the inaugural running of what has become the Super Bowl of Bass Fishing.

What is even more momentous about that landmark event is the fact that catch-and-release bass fishing came into being there.

At one of the evening functions at Lake Mead, B.A.S.S. founder Ray Scott announced his “Don’t Kill Your Catch” campaign.

As Bob Cobb records in his new, must-have book, The B.A.S.S. Story — Unplugged (xlibris.com), catch and release debuted at the Florida Invitational in 1972, with some success. As boat builders and others figured out how to aerate livewells, it grew in success and popularity. Today, almost half a century later, the vast majority of recreational fishermen release all or most of the bass they catch.

It has since grown into a universal standard that has helped maintain quality fishing worldwide. Arguably, fishing is better now in many lakes than it was in the ’70s, thanks to the catch-and-release ethic.

Taken to its extreme, though, catch and release is not good for the sport.

My bass fishing mentor, the late pro angler John Powell, used to tell me, “Y’all keep harping on catch and release, and pretty soon they won’t want you to catch ’em at all.”

“Germany has outlawed catch and release altogether,” noted Gene Gilliland, B.A.S.S. conservation director and a former assistant fisheries chief in Oklahoma. “It’s considered cruel to fish for sport and only marginally acceptable if you eat the fish.

“The pendulum has swung too far to the total catch-and-release side in my view,” Gilliland said. “There are fisheries around the country where harvesting fish would be appropriate and beneficial to the health of the bass fishing population.”

During our conversation, Gilliland was managing fish care at the Toyota Bassmaster Texas Fest benefiting Texas Parks and Wildlife Department at Lake Fork, Texas — where the catch/weigh/instant release tournament format was born 13 years ago, and where it lives on in Texas Fest.

At that legendary big-bass factory, bass longer than 16 inches and less than 24 inches must be released.

The goal is to protect the most prolific spawners while removing smaller bass, but almost no one keeps the “unders” there, he said.

The slot regulation at Fork necessitates the immediate-release format pioneered by TPWD and practiced in Texas Fest, but that doesn’t mean the time-honored format in which anglers bring their heaviest five bass to the weigh-in stage is wrong.

“Yes, a few individual fish die as a result of tournament fishing,” Gilliland acknowledged. “But if you look at the entire bass population of a lake, we don’t see any negative impact.”

That impact has been minimized even further thanks to advancements in livewell technology, the new Yamaha live-release boats and other fish-care practices outlined in the Keeping Bass Alive handbook, coauthored by Gilliland in 2002.

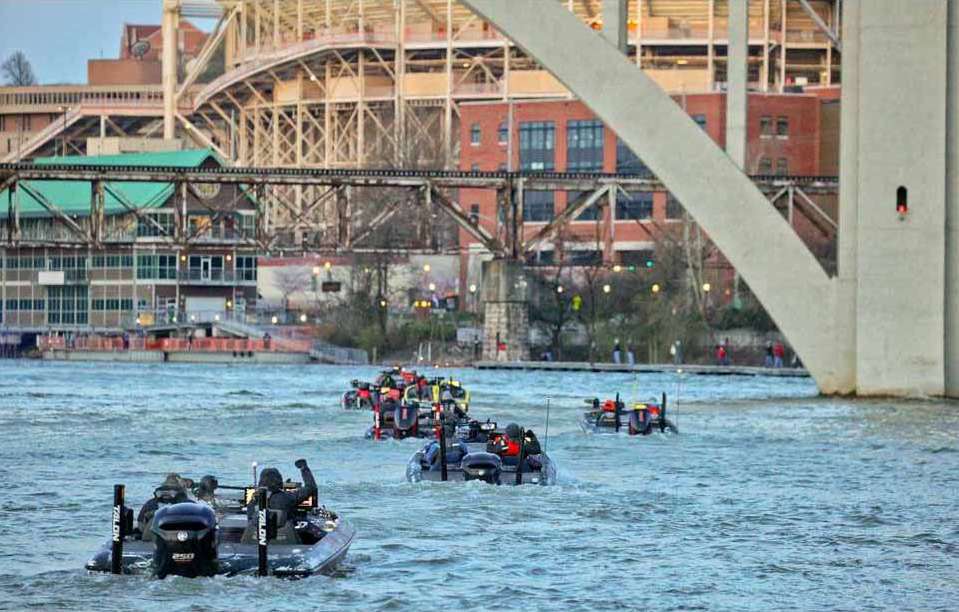

At this year’s GEICO Bassmaster Classic presented by DICK’S Sporting Goods in Knoxville, Tenn., all but one bass out of the 521 fish weighed in were released back into the Tennessee River.

And the fishery, study after study has shown, is none the worse for it.