Drinking straws, beverage bottles and product packaging are some of the common plastics that are now degrading inside the Tennessee River system and other freshwater streams. Once in the water, the plastic waste slowly degrades into smaller particles that are often ingested by fish.

The concern is that microplastics act as super magnets to absorb concentrated amounts of toxins that are suspended in minute levels throughout most all public drinking-water sources. The University of Tennessee (UT) is studying the potential impact of these toxins by trawling for microplastics inside the entrails of a small school of some 3,000 preserved fish.

The first-of-its-kind study hinges solely on the university’s on-campus pickled-fish museum, known as the David A. Etnier Ichthyological Collection. The archive is essentially a 45,000-jar library that contains an estimated 420,000 specimens from the Tennessee River. The fish samples — originally collected by both Tennessee Valley Authority biologists and university students — date as far back as 1965.

Tissue samples taken from some of these specimens are helping UT determine if ingested microplastics can contaminate edible parts of a public food source. Researchers are also mapping the decades worth of pollution data they are finding trapped inside many of the fish. The work is helping the team better understand whether microplastics can disrupt the underwater food chain by harming fish offspring or increasing their mortality rate.

There is currently no evidence that suggests the presence of microplastics in freshwater streams pose a direct danger to human health or the environment. But that may simply be because — unlike heavy metals, chemicals, harmful bacteria and other freshwater contaminants — no state or federal authority monitors or regulates microplastics pollution in the United States.

To date, no freshwater long-term studies on microplastics pollution have been conducted. Only limited saltwater research exists, and the results are largely non-conclusive.

UT hopes to fill the void by publishing its comprehensive findings by fall of 2021.

The Tenneswim findings

Studying preserved fish is all about plotting new data. And to get it, UT’s biologists are taking a deep dive into a microplastics discovery that occurred in 2017.

The find came when Dr. Andreas Fath, a water chemist from Germany’s Furtwangen University, secured a pollution sensor to his wetsuit and swam the entire 652-mile Tennessee River for science. He completed the education initiative with the help of a small team of scientists and students from the University of the South at Sewanee, Tennessee.

Dr. Fath’s 34-day, long-distance soak drew international recognition and bolstered public awareness to the drinking-water source of more than 5 million people. The Tenneswim study revealed large amounts of microplastics pollution throughout the Tennessee River and confirmed that suspended toxins do in fact bond to microplastics in concentrated amounts.

“If a microplastic particle can have 100 even 1,000 times the concentration of harmful pollutants, could that same microplastic dissolve throughout the fish?” Dr. Fath said. “Is it a problem? We don’t know. That’s why conducting this research is so important.”

Dr. Ben Keck, the Etnier Collection’s director and curator agrees.

“When I saw on the news about Dr. Fath’s swim, I knew UT had the perfect resource to take the Tenneswim research further,” Dr. Keck said. “Using the Etnier Collection for this study not only benefits our students, but it’s providing valuable microplastics data for the entire world.”

What’s the big deal?

The Tennessee River system is one of the most bio-diverse freshwater natural resources in the world. It is home to more than 350 known fish species, and is a recreation asset that provides a critical economic benefit to the Tennessee Valley.

According to a 2017 TVA/UT study, the Tennessee River supports 130,000 jobs and hooks an estimated $12 billion in annual revenue throughout the region.

Three of its reservoirs — Guntersville, Pickwick and Chickamauga — are ranked among Bassmaster Magazine’s “Top 25 Best Bass Lakes of the Decade.” And the Bassmaster Classic, which is often regarded as the sport’s pinnacle attraction, generated $32.2 million for the host city of Knoxville in 2019.

In short: The Tennessee River Watershed is a prized natural resource that must be protected.

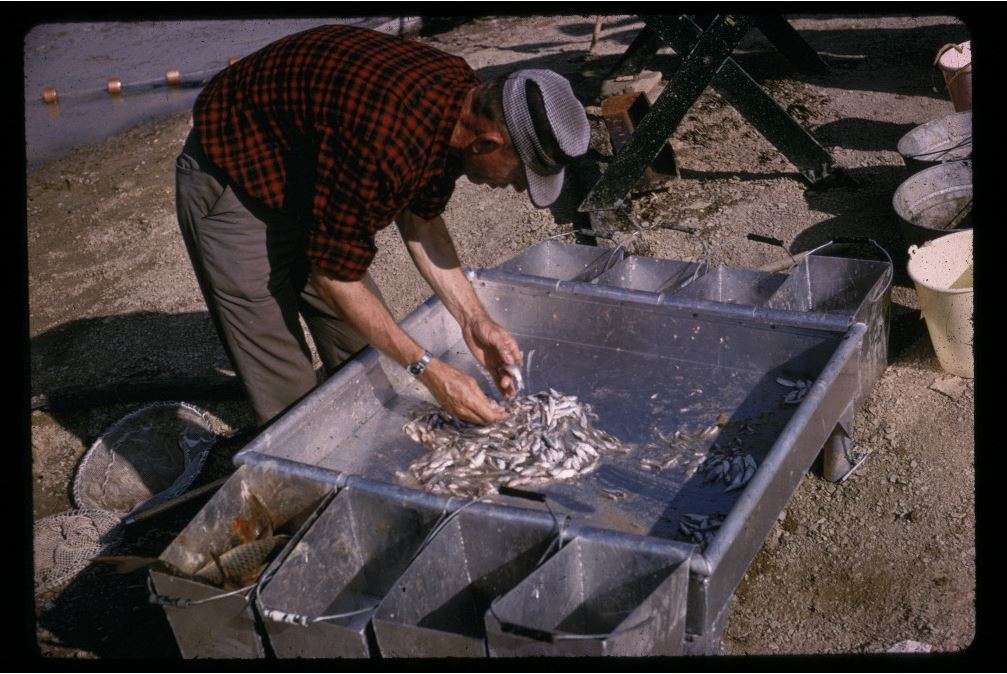

However, the job requires foresight. That’s why TVA and UT biologists are focused on studying small fish, such as minnows and darters.

“The changes or patterns we discover in these fishes are often early indicators of potential problems that might be developing in our rivers,” Dr. Keck said. “The science gives us the ability to raise the flag and hopefully correct water-quality issues before they ever have a chance to become a concern. That’s why we are studying microplastics pollution in fishes.”

Details of the microplastics study

Dr. Keck says the depth of UT’s fish library is the key to understanding microplastics pollution. Not only is the Etnier Collection a trove that holds decades of environmental records for the entire 40,890-square-mile Tennessee River Watershed, but it preserves multiple species of fish that live, feed and reproduce in various parts of the ecosystem.

The museum’s diversity is critical to UT’s study, because it gives biologists and students access to fundamental links in the underwater food chain. By extracting microplastics particles and fibers that are lodged or have been ingested by three types of fish — a stoneroller minnow, white-tail shiner and black bass — the team is mapping generations of pollution data across a large-scale gradient.

“Our great-grandfathers weren’t thinking about microplastics, but because they had the foresight to fill a bunch of jars with creek minnows and formalin, we’re now reading the Tennessee River’s entire microplastics story,” Dr. Keck said.

He says it’s simple. Each of the museum’s jars — referred to as a “lots” — is essentially a time capsule that holds an environmental snapshot of the river. If they want to know what type of microplastics were in the water in 1977 or 1992, all they have to do is look inside a few fish that were pickled during those same years.

“We’ve pulled lots every five years, all the way back to 1965,” Dr. Keck said. “We’re studying nine specific locations upstream of Chattanooga.”

Polyester, for example, is a common microplastic fiber that the team is finding hung inside the fishes’ gills. And polyethylene, which is the standard material of plastic packaging and the everyday grocery bag, is showing up in the bellies of many specimens — some collected as recently as the 1980s.

The presence of polyethylene is not a surprise. According Dr. Martin Knoll, the Sewanee geology and hydrology professor who helped conduct the Tenneswim survey, about half of the Tennessee River’s microplastics pollution is polyethylene.

“Bottom line is that the Tennessee River is a pretty darn clean river. It’s got low levels of everything except microplastics,” Dr. Knoll said. “It’s not a divisive or political subject…. Everyone wants clean water, but there is no way to get a definitive answer about microplastics until we go out and test it.”

Will UT find the answer? No one knows. The only certainty is that it takes time to dissect 3,000 pickled fish for pieces to an unsolved puzzle.