PHOENIX, Ariz. – For two years, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) has been assessing whether to allow the states to once again cull troublesome cormorant populations on public waters. As that investigation drags on and many voice concerns, Arizona is asking anglers to help determine the impact of these fish-eating birds on waterways in that state.

“Data shows that fisheries around the country have been greatly impacted as cormorant populations continue to grow,” said Chris Cantrell, Fisheries Branch chief for the Arizona Game and Fish Department (AGFD).

“As cormorant numbers increase throughout Arizona, we must study to see what impact this will have on wildlife and our fish populations. This research will better position us to learn what we can about these birds to prepare for the future and to develop sound management techniques.”

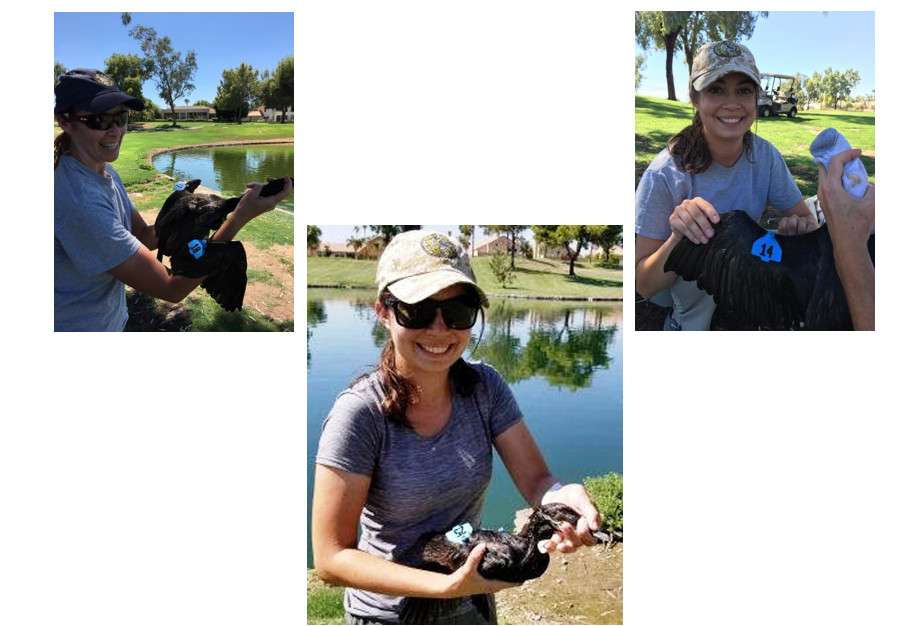

To enable that study, resource managers have tagged cormorants, and fishermen and others are asked to report when and where they see them.

“Cormorants are highly adaptable birds and, we wish to learn more about them,” added Larisa Harding, program manager for Terrestrial Research. “We need to learn how these growing populations are connected to the landscape, their migration patterns and what impact – if any – their increasing numbers are having on other wildlife, including area fish.”

Meanwhile, others across the country report that cormorant numbers are increasing and they are having an impact, but it might not be because of what most anglers suspect.

“I’ve seen more cormorants in the past couple of years than ever before,” said Scott Sewell, conservation director for the Maryland B.A.S.S. Nation. “Their numbers are increasing at an alarming rate.”

Tennessee biologist Tim Broadbent added that he isn’t yet seeing large roosts on Kentucky Lake, but said that their numbers have increased during the past decade.

“They eat a lot of shad,” he continued, citing a Kentucky study of stomach contents in 850 of the fish-eating birds.

“It was 55 percent shad and a few silver carp, with bass and crappie making up less than 1 percent,” the biologist said. “Sunfish numbers were higher in May.”

When cormorants aren’t eating fish, however, they nest in large numbers, defecating on trees and surrounding vegetation, and that is causing problems in many places.

“Their droppings change the pH (of water) and everything dies,” explained Frank Fiss, fisheries chief for the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. “Then you have erosion, and that kills islands.”

Mike Hays of Blue Bank Resort on Tennessee’s Reelfoot Lake added, “We’re losing a whole lot of habitat.

“In five years (if controls are not implemented), we’re going to lose all of these (cypress) trees, and many of them are 200 to 600 years old,” he said. “They were here when the lake flooded. They survived back then because they already were so tall. And, once they’re gone, unlike the fish, they can never come back.

“What makes it so bad is that once these birds kill trees in one area, they move on to another. Right now, they’re killing groups of trees in some of the most fished areas.”

Environmental damage also is occurring at Vermont’s Lake Champlain, where resource managers no longer are allowed to shoot the birds or oil their eggs to keep them from hatching. “It will not take very long for the number (of cormorants) to double without some active management,” said Mark Scott of the Vermont Department of fish and Wildlife.

“They nest in very large numbers, and they kill trees on islands in the lake,” added Dave Capan, who has been managing the cormorant program on the Four Brothers Islands. “There are at least five or six islands in this lake that have lost most of their trees and vegetation.”

On Lake Erie, a cormorant colony of 20,000 has wiped out an estimated 40 percent of the tree canopy on Middle Island.

Why is this happening?

Until May 2016, FWS issued depredation orders to states, allowing them to kill up to 160,000 double-crested cormorants annually. For example, to protect islands in Kentucky and Barkley Lakes, resource managers were allowed to take 300 annually. With a much larger problem on Santee-Cooper, South Carolina staged a public hunt that culled about 40,000 in three years.

But then bird conservationists and environmental activists successfully sued to stop the issuance of those orders. The U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C., concluded that FWS did not take a “hard look” at the effects of the depredation orders on double-crested cormorant populations and other affected resources and failed to consider a reasonable range of alternatives in the environmental assessment issued in 2014.

“In the meantime, our cormorant depredation permits were invalidated by the court order and individuals have to seek an individual permit with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,” said Craig Bonds of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. “This is basically the same process people had to go through prior to 2004, when we (and other state agencies) were granted the authority to issue our own permits.”

Consequently, according to FWS, it now is engaging with “states, tribes and other stakeholders to assess the biological, social, and economic significance of wild fish-cormorant interactions.

“This will includ identifying the monitoring needs necessary to address the issue and gathering better scientific information that could be used in the NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) review and decision-making process.”

This growing problem exists because double-crested cormorants, along with 800 other species, are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 and subsequent amendments. Intent then was to protect birds that migrated across Canada and the U.S. from commercial overharvest.

But that did nothing to protect them and other fish-eating birds from the devastating effects of the pesticide DDT, and populations plummeted. DDT didn’t kill the birds, but rather altered the birds’ calcium metabolism so that their eggs thinned and couldn’t support the weight of incubating parents.

But populations of fish-eating birds rebounded when the pesticide was banned. Additionally, for cormorants at least, thousands of reservoirs built on the nation’s river systems provided far more habitat and forage than they had historically. With that combination, populations exploded during the 1970s and 1980s, especially on the Great Lakes. And spreading out from there, they’ve established huge colonies all the way down to the Gulf Coast.

Mostly, they’ve been vilified for eating too many fish, and, in some cases, that accusation has been justified. Much of the damage that they do to fish populations, however, is centered around hatcheries and put-and-take stockings of sport fish, especially trout and salmon. For example, they eat millions of salmon smolts annually in Washington and Oregon, posing a far greater threat than predation by smallmouth bass.

This spring, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife will coordinate a cormorant harassment campaign along the coast.”Hazing will involve driving the birds from locations where juvenile salmon are seasonally concentrated, toward areas where non-salmon fish species are more abundant. Workers will use boats and on some estuaries, small pyrotechnics, to accomplish the task,” the agency said.

“Hazing is intended to increase the survival of both wild-spawned and hatchery salmon juveniles as they migrate to the ocean. Some of these spring migrants represent species that are experiencing conditions of conservation risk, including coho salmon, which is federally threatened in Oregon under the Endangered Species Act.”