I’ve been fishing B.A.S.S. events for more than 35 years. I started with the Invitationals, then progressed to the Top 100s, Top 150s and eventually the Bassmaster Elite Series. Throughout that time and in all of those hundreds of competitions, I was never asked to submit to a polygraph exam.

However, that streak ended when my name was drawn during the recent Lake Chickamauga Elite Series event.

As I approached the weigh-in line on Day 1 of the competition, Senior Tournament Director Chris Bowes informed me that my name had been randomly selected, and that I was to accompany him immediately after my fish were weighed.

For some, that would have sent chills up their spine. But for me? I was actually looking forward to the test.

B.A.S.S. rules

The Bassmaster Elite Series rulebook states, “By signature of the Elite Series participation agreement or an official entry form, each competitor agrees to submit to a truth verification test and abide by its conclusion…” It goes on to say, “Failure to pass a truth verification examination is not appealable.”

Besides random selection, a competitor may also be subjected to a polygraph if he or she is protested by another angler. That can include a number of infractions, such as not obeying the no information rule or breaking local, state or federal laws during the event – to include each practice and competition day.

Although protests are rare, they do occur. And it’s a tedious process to complete.

First, the protest must be filed immediately in writing, not days after an event. Once the protest is received, tournament officials will investigate while reserving the right of when or if to act on the protest. If the evidence is substantial or leaves any doubt, they then have the right to impose a polygraph – which is given by an independent, certified professional.

When the exam is completed, the tournament director then has the right to levy punishment in the form of fines or disqualification, and then publish the results.

Again, these are rare occurrences, but they do happen.

Truth or consequences

As Chris Bowes escorted me to an off-site location for the exam, I wondered what the protocol might include. To that point, I had only heard brief inferences from other anglers who had been tested or knew someone who had been tested. And hearing those stories only made me more curious.

Once at the location, I was introduced to the examiner and briefed on the procedure. That included a “dry run” of questions he intended to ask.

Most were fairly mundane, such as “Did you report BassTrakk weights accurately and to the best of your ability?” and “Did you observe normal safety precautions during the event?”

Then came the more probing questions.

“Once the tournament was announced, did you intentionally gather waypoints or any specific fishing locations from a source not available to the public? (Note: Elite Series competitors are allowed to gain information shared on public platforms, such as fishing reports in magazines or websites, etc., but not from sources unavailable to the public.)

“Did you pre-fish with anyone having knowledge of the tournament waters?” (This rule goes into effect once the tournament schedule is announced in any given season, and it’s designed to keep the entire field at the same disadvantage.)

Finally, “Did you answer all of the questions in this interview truthfully?”

Protocol requires the exam to be conducted twice, which took maybe 45 minutes or so. And of the dozen or so questions asked, my answers were truthful and completely vindicating. Although I expected that would be the case, it was still somewhat relieving to hear it from the examiner.

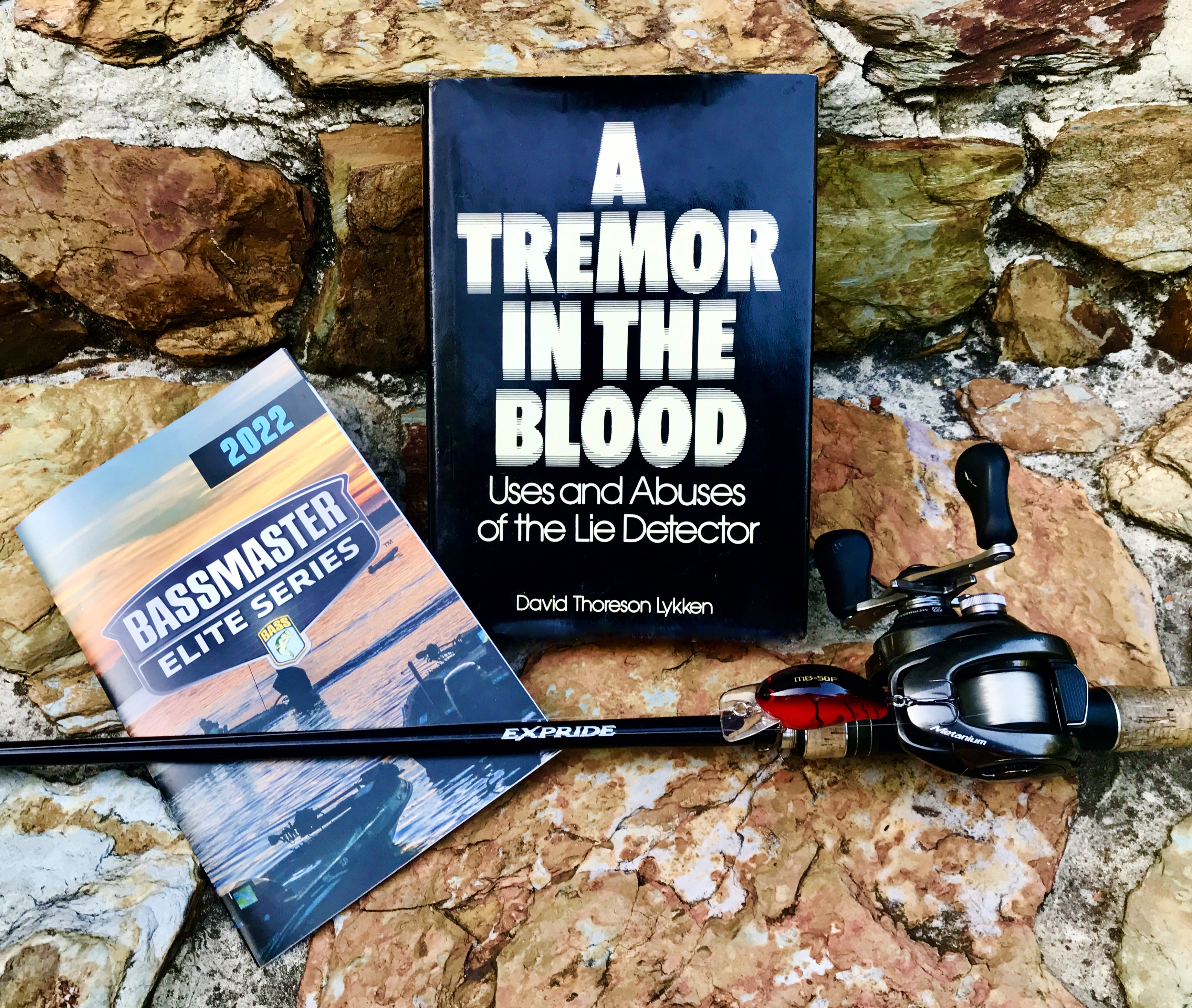

A tremor in the blood

So how effective are polygraph exams? The answer depends on who you ask.

In his book, A Tremor in the Blood, author Dr. David Lykken claims there is a 50/50 chance of innocent subjects failing the test — siting actual cases of people whose lives were destroyed as a result. The book also explains how criminals and others skilled at deception are able to beat the test.

Although some state level courts consider polygraph results as permissible evidence, most do not. The latter believe them to be inconclusive and unreliable. Lykken points that out in his book, as well.

It’s important to note that the largest number of polygraph examinations are conducted in the workplace — by employers screening job applicants, hoping to better assess character traits, etc.

So in the context of tournament fishing, are they necessary? One would like to believe the rules are always observed. Unfortunately, they are not. So, it’s essential to have some sort of deterrent. And, for now, a polygraph is the only real option.

Follow Bernie Schultz on Instagram, Facebook and through his website.