Kevin Gaubert is president of the Louisiana B.A.S.S. Nation, so he gets regular reports from anglers about the hottest fishing spots and the latest lures to catch the biggest bass in the Bayou State.

Gaubert is also a property owner in south Louisiana. He lives in Luling, which is a tiny town tucked beside the Mississippi River only a few miles west of Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport. It may sound cliché, but he’s a proud American, and he values his right to live on his own property and do with it pretty much what he pleases.

These days, Gaubert is hearing as much about property rights as he is about bass fishing, and that’s cause for alarm, he said.

The calls started flooding in shortly after B.A.S.S. announced in August it would not allow Bassmaster Elite Series anglers to fish in Louisiana waters during a tournament scheduled to be held in April 2018 on the Sabine River – the state’s western border with Texas. That tournament is scheduled to be headquartered in Orange, Tex., but that city is only a few miles inside the Louisiana/Texas border. Without a doubt, many Elites likely would have fished in fertile Louisiana water as they have done in previous tournaments on the Sabine.

Officials with B.A.S.S, the world’s largest bass fishing organization, said it was a tough decision to keep anglers off Louisiana water, but one that was necessary. B.A.S.S. cited difficulty with Louisiana’s unique laws that allow landowners to claim as private any tidal or moving water that runs through their property. Under current Louisiana law, that means the overwhelming amount of water on the state’s coastline, and neighboring rivers and bayous, is technically offlimits to anyone except the landowner and invited guests.

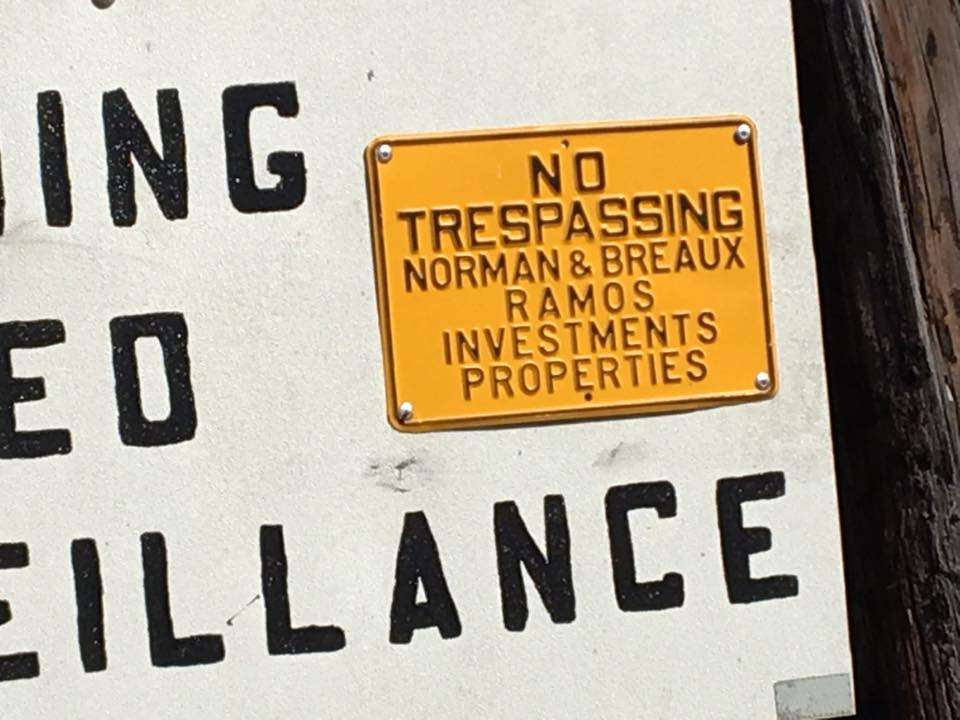

And Gaubert said a rapidly increasing number of property owners indeed are laying claim to chunks of brackish marsh and intersecting waterways all along the coast. Some have gated canals that lead from public spaces onto private land, and others have asked for help from local law enforcement agents to keep trespassers from their land and the water cutting through it. Many tickets have been written and there are some who say anglers have been threatened with lawsuits, jail or worse if they dare return.

Those practices are treasonous to many of the hundreds of thousands of Louisiana anglers who take fishing as serious as LSU football. They say that because state law doesn’t require landowners to post their land, it’s nearly impossible to know when water is public or private. They say the ever-shifting coastline rearranges property lines on a daily basis and that shorelines they once fished have slowly deteriorated into open water (which long has been considered fair game to all anglers).

There has been passionate discourse from both sides, but Louisiana’s law on the matter remains vague to many and unchanged for all. And so the battle of wills continues, with landowners fighting for the right to manage and preserve their property as they see fit. Many say anglers encroach on their land, they disturb lucrative duck and deer leases and that Mother Nature makes nothing easier by continuing to take her own share of their land through erosion, subsidence and sea rise.

Meanwhile, many anglers insist their taxes also pay for fish and game management and that should make wildlife an asset for everyone to enjoy equally. Some also believe that property owners are as much as factor in land loss as saltwater intrusion and erosion.

“There are so many [posted] signs going up, and none of it looks official,” Gaubert said. “They’re hand-painted. People don’t have documents. It’s some cases, it’s just people running people off. People get letters in the mail from lawyers saying we’re going to prosecute to the fullest extent of the law. If it’s tidal water, you’d think that everything that goes with it – the fish, the wildlife – that’s all of ours. But when it goes on their land, it’s theirs. The land rights I can see, but the water? It just doesn’t make sense. If you can move a boat through it, I think we should have access to it.”

All of this is happening in a state where 91 percent of the land is privately owned, and even still, there remains enough premium public water to make south Louisiana in particular one of the finest fisheries on the planet. Some expect great fishing will continue whether B.A.S.S. decides to hold a tournament in coastal Louisiana again or not. After all, the state’s public/private water laws largely have remained the same since Louisiana joined the union in 1812, so why change what has fostered a practically unparalleled fishery for more than 200 years?

Gaubert said, however, that focus on the public/private issue has intensified in the past three years, and it’s truly become a hot-button topic since August. Local and national media picked up on the story then, and social media continues to buzz with anticipation of change. A petition is circulating throughout Louisiana’s vast network of fishing guides and weekend anglers with the ultimate goal of bringing permanent change to the public/private issue once and for all.

Some observers said a resolution could come on the subject as early as next year. Others say it may never happen.

So the haze lingers.

“Other states have laws that allow access to any waterways that are navigable,” said Rebecca Triche, executive director of the Louisiana Wildlife Federation. “But that’s not the way it is here. All that could be changed by law, but is it going to be? [The issue] is vast and it’s difficult.”

Playing the game elsewhere

Louisiana has been one of the most frequent tour stops for B.A.S.S. through the years. Six GEICO Bassmaster Classics presented by DICK’S Sporting Goods have been held in the state since the inaugural tournament was held in 1971, with four of those staged in the vast Mississippi River Delta. South Louisiana hotspots such as the Atchafalaya Basin and the Sabine also have been home to successful Elite and Open events in recent years.

Those fisheries would be the areas hardest hit by the B.A.S.S. decision to avoid scheduling tournaments of any kind in south Louisiana until the public/private issue is resolved. B.A.S.S. officials said areas such as Toledo Bend and the Red River (which hosted the Bayou State’s other two Bassmaster Classics) will not be abandoned as possible tournament sites, as they are not affected by coastal tides or the hubbub taking place a couple hundred miles south.

Still, the decision is expected to hit the state’s fishing tourism industry in the pocketbook. Smaller communities on the coast reap hundreds of thousands of dollars when they host a B.A.S.S. tournament, and each receive tremendous exposure that reels in anglers from across the U.S. And that pales in comparison to the loss of a future Bassmaster Classic which would torpedo a potential $20 million local economic impact.

Dave Precht, Vice President of Publications and Communications at B.A.S.S., said the decision was difficult given the organization’s history in Louisiana. Still, he said it’s imperative that every tournament have a level playing field and B.A.S.S. isn’t sure that can happen in Louisiana right now.

“It can’t be confusing,” said Precht, who is a Louisiana native himself. “We wish Louisiana had the same interpretation of waterways as other states, but it doesn’t. In those places, if you can float a boat on it, it’s public. In Louisiana, the private water doesn’t even have to be posted. It’s not fair to our anglers to go into a tournament, find a spot they want to fish, catch fish one day, then go back the next and find a sheriff’s deputy ready to arrest them if they come back in.”

That didn’t happen on the Sabine in the Bassmaster Central Open No. 2 in June, but there was unpleasantness still.

“Local Louisiana authorities came to tournament director Chris Bowes and told him there were a couple areas right near the launch that would be offlimits,” Precht said. “These weren’t tucked off somewhere deep in the marsh. They were right off the main canal. People were crossing through it to get to public waters. We had guys catching bass there in practice too.”

Gaubert said it’s not only the big groups such as Bassmaster Elite and Open events that are being affected, either. He said finding suitable spots for the B.A.S.S. Nation tournaments can be a difficult job too these days.

“It’s a headache for B.A.S.S. and I understand why they don’t want to come,” Gaubert said. “Morgan City [in the Atchafalaya Basin] had some really great areas. Now it’s all gated off. [In our B.A.S.S. Nation events] if you have a run in with a landowner and you get a ticket, you’re going to be disqualified.”

Perfect landing

Like Gaubert, Paul Frey is an outdoorsman and a property owner. Frey also is the president of the Louisiana Landowners Association, and he has a different view of how things are happening in the coastal marshes.

“The bottom line is fishermen, especially on the commercial side like the guides, they are primarily looking for access to private property,” Frey said. “This property has been managed and protected by landowners and in many cases, it’s been leased to hunters, to crabbers, to oystermen, to people collecting gator eggs. There’s even some of the property that’s been leased to fishing guides who have private access.

“But [to say the public fish areas] are shrinking is incorrect,” he said before reeling off a list of nearly two dozen large wildlife management areas, public lakes and rivers from all points across Louisiana.

“I keep hearing there are fewer public places,” Frey said. “I just don’t see it.”

Frey said trespassing alone is reason enough to keep anglers off private property, but he said damage to marsh and land, as well as overuse of the asset, are other reasons that galvanize the need to protect landowner rights. He cited a case in which a frogger was trespassing on an oil canal, ran into a bulkhead and was injured. He sued the oil company and the landowner.

Frey also said posting private property is senseless because more often than not “the signs get shot or torn down,” he said. “You go to the expense and effort to post it, and in two weeks it’s gone.”

Frey compared Louisiana’s main waterways to roads motorists use every day. Turn off the main drag and you’re likely in someone’s proverbial front yard, he added.

“When you turn into someone’s driveway [or into a canal] you’re likely on private property and are trespassing.”

And to Frey, that makes public/private an open-and-shut case.

“I’ve hunted and fished on our coast since I was 14 or 15 years old,” said Frey, who now is in his 60s. “There have been a lot of changes to our coast. But when it comes to the opportunities to fish, it just escapes me why there is so much flak out there right now.”

Frey also is perplexed why B.A.S.S. made the decision to shy away from the south Louisiana fishery.

“My question is ‘Why? Why now?’ Nothing has changed here. The laws are the same,” Frey said. “I hate to say it, but I think that B.A.S.S. is drinking the Kool Aid of social media. We have extensive public water in Louisiana. And people say you don’t pay taxes on water in Louisiana…‘Oh yeah? Let me show you the bill.’”

No place like home

Greg Hackney is one of the finest Elite Series pros on tour and he calls the Baton Rouge suburb of Gonzales home. He’d love the chance to fish an Elite or Open event in his home waters, but he said he’s afraid that might not happen again.

Hackney may have a point. The private/public water issue is not new and it is not without controversy. Still, nothing about it has changed in years, except of course to remove the requirement that land owners post private property.

Like Gaubert, Hackney is frustrated.

“I understand both sides of it,” he said. “We have a right to own property in America, and I don’t want anyone messing with that. I have a house and a yard, and I don’t want anyone coming up in there. But I think the water is public, and we all pay taxes on it. So if they aren’t going to let you fish all of it, then dam up the private canals. Keep the fish in public water.”

Admitting that’s far-fetched, Hackney did agree with Frey that there is ample public water in Louisiana to fish no matter what methods property owners do to keep anglers out.

“There are hundreds and hundreds of thousands of acres where the fishing is great and there’s no doubt it’s public,” Hackney said. “I was going to pre-fish the Lacassine area [in southwest Louisiana] to prepare for the tournament on the Sabine last year. You can catch 10-pounders in there…I just hate the whole deal for the state. It’s just such a great place to fish. It’s a shame we’re probably not going to [fish south Louisiana in the immediate future]. I’d like to fish one at home.”

Gaze into the crystal ball

Hackney still may get that chance, some observers agree. Groups such as the Louisiana Sportsmen’s Coalition have been at the vanguard of promoting angler rights, and representatives of that group, guiding organizations and others sat down with the Louisiana Landowners Association this summer to exchange ideas of how a solution that benefits all could be reached.

A state legislator helped pass a resolution that will allow the Louisiana Sea Grant, part of the National Sea Grant Program based at LSU, to conduct those meetings and future discussions on the issue. Those talks were described as beneficial, but some have said an agreeable interpretation of Louisiana’s law may be several more years in the making.

Precht said it’s not unprecedented for states to overturn fishing laws that make groups like B.A.S.S. look elsewhere for tournament venues. He said Florida passed a law not too long ago that heavily taxed tournament winnings. B.A.S.S. balked and began holding fewer tournaments in the Sunshine State until the law was overturned. Precht is hoping the same thing happens in Louisiana.

“I’m trusting something will happen in south Louisiana,” he said. “It does seem to have more momentum than other times. A lot of people seem very much in favor of changing the laws.”

New Orleans resident, outdoorsman and Pulitzer Prize winner Bob Marshall said that may be the case, but change definitely will take time. He said the marsh’s greatest culprit remains erosion, and that’s detrimental to both landowners and anglers.

“Where your marsh becomes open water is where I have access to it,” Marshall said. “But even further complicating the matter is that when we rebuild marsh, the rebuilt marsh reverts back to the landowner…This is coming everywhere in the U.S., we’re just more advanced because of our unique and tragic coastal issues…We’re making more fishermen but not more shorelines. As the population grows, you’re going to see this more and more where public water is up against private property.

“Louisiana has to come to grips with this,” Marshall continued. “Some kind of law needs to be passed now before someone gets hurt.”