During the transition between summer and fall, the bite can be tough. Five Elites explain how to not only get bit, but how to get the biggest bites

It’s transition time in much of the country, and bass are starting to shift gears from their summer patterns to a fall feeding focus (Florida being the exception). Five Bassmaster Elite Series anglers shared their insights into how they track down and engage early fall giants.

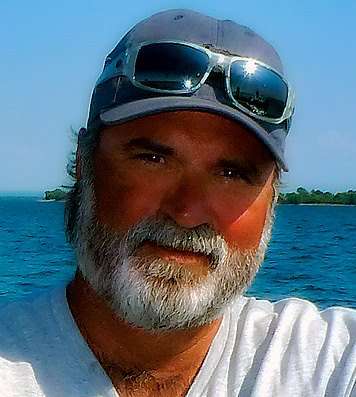

Shane LeHew

Recognizing that this transitional season is a tough time of year to target giants, LeHew still believes he can get it done. For him, it’s a matter of intercepting fish that are following the leading edge of the fall baitfish migration.

“I’d probably fish pockets and try to get around some bait,” LeHew said. “A lot of times, the shad start moving into the backs of creeks, so those big fish will be following the food that time of year.

“Typically, on reservoirs, the longer creeks [excel]. It’s probably an oxygen deal; you’re in that fall transition where the water temperature is going to start to decline a little bit. I think the bait is just chasing that oxygen, and the largemouth, smallmouth or spots — whatever you’re fishing for — will follow that bait.”

LeHew likes to target the bigger fish with the noisy, sputtering Berkley Choppo 120. Favoring the bone or perfect ghost colors, he’ll fish this big-fish bait over the shallow flats where the giants use random pieces of washed-up wood as ambush spots. Light wind and sun is the formula for success, especially in clear-water scenarios.

“A lot of them will be cruising in wolf packs,” LeHew said. “Typically, your bigger fish will be the ones in the wolf packs.

“I like to make pretty long casts because sometimes those really big fish will be pretty shallow. I like a steady retrieve on that Choppo — nothing too crazy, but I’ll fish it on an 8.3:1 reel, so if one misses the bait, I can quickly reel it in and make another cast.”

Notably, LeHew said he’s not terribly concerned with time of day, as this fall transition can find the fish chewing from sunup to sundown. The key: Staying with the food flow.

“If they’re not coming to the bait, I’ll have a backup like a wacky-rigged Berkley MaxScent The General in green pumpkin or shad or a shaky head with a green pumpkin Berkley Bottom Hopper worm,” LeHew said. “Typically, the bigger fish get that [Choppo]. If they’re reacting to it at all, they’re going to get it.

“Even if a few miss it, I still feel like I can catch a bigger one on it. In the fall, if you’re covering enough water, you’re going to run into a big fish.”

BAIT: Topwater

WHY: Covers water

WHERE: Shallow flats

Mike Iaconelli

From the Potomac to the Mississippi, Iaconelli knows the hunt for giant river fish follows a similar course.

“Whether I’m fun fishing or in a tournament where I have my limit and I need a big one, my rule of thumb for targeting big ones is [to] fish deeper than I typically do and thicker than I typically do,” Iaconelli said. “In rivers, whether it’s the Delaware, the Hudson River or the St. Johns, I hardly ever fish deeper than 5 feet because I believe the mass population of fish live shallow in rivers a lot of the year — they have everything they need.

“I think the mentality of those big fish is they don’t want to compete with the 2- and 3-pounders. They’re big loners that want to be by themselves.”

Iaconelli mostly looks for his bigger river fish in channel bends, where accelerated current washes out greater depths. Using the James River as an example, Iaconelli wants to find key structure like cypress trees right on the edge.

“I have some cypress trees on the James that go directly down into 15 feet of water,” Iaconelli said. “That’s the tree for a big fish. The other trees in 5 feet or less, those are my number trees.

“I’ve done this on docks, laydowns, grass edges, where that deep water touches. The bigger forage is always there, and that deeper water gets very little pressure. That fish can be on a tree root in 8 feet and, with a flick of the tail, he can be in 15.”

Iaconelli’s deep-water river arsenal starts with a Texas-rigged Berkley Chigger Craw, Berkley Havoc Pit Boss or Berkley MaxScent The General — each weighted appropriate to the targeted depth. He’ll also fish these baits on a 1/4- to 3/8-ounce shaky head and, if the bottom’s heavily silted, a 3/8- to 5/16-ounce VMC Tokyo Rig keeps the bait visible. Throw a deep rockpile into the mix and Iaconelli’s throwing a Rapala DT8, DT10 or DT14.

“For thicker cover, I try to fish farther into it than the average guy will fish,” Iaconelli said. “I’ll find the thickest, nastiest, gnarliest cover I can find. With matted vegetation, I’m not fishing the edges; I’m fishing as far back into [it] as I can.

“This also applies to wood — logjams and smaller debris mats. Try not to make that easy outside cast, but cast far into the wood. I’ve caught some of my biggest fish in the Delaware River under trash mats.”

For his thick-cover work, Iaconelli will punch through with a Berkley MaxScent Creature Hawg Texas-rigged on a 3/0 VMC hook and a 1-ounce VMC tungsten weight. Another option: a 3/4-ounce Missile Baits Ike’s Flip Out jig.

“Sometimes in warmer water, you want to let them come up and get [a bait],” Iaconelli said. “I’ll throw a Molix Pop Frog into that mat, and I’m trying to put that frog where nobody else puts it.”

BAIT: Texas-rigged craw

WHY: Weedless

WHERE: Thick, deep cover

Scott Martin

Of all the phrases we use to describe largemouth bass, few can rival the foundational wisdom of: “They don’t get big by being dumb.” Martin agrees and applies this truth to the where/when of tidal bass targeting.

“I like a mid-to-low outgoing tide, which is going to position those fish to the outside cover,” Martin said. “Those bigger fish like hard cover, and that could be dock pilings or a laydown tree, so when I’m looking for a big fish, I’ll target these places more so than marsh drains and grass edges.

“When the tide’s up and high, those fish spread out, but the dinner bell’s ringing hard on a mid-to-low tide. You may have a dock with 15 pilings and it’s 4 feet on the end of it and 2 feet at the back side. They could be anywhere during high tide, but [lower water] forces them out to the outside pilings.”

While Martin knows he can fill a limit by pitching a worm, he’s confident he can generate his biggest bites on moving baits. He prefers a Googan Banger squarebill or a 3/8-ounce ChatterBait with a double-tail trailer or a 3/8- to 1/2-ounce Googan flipping jig with a double-tail craw trailer.

“I’m going to throw the squarebill on lighter cover like one log or one or two sticks or one piling, but if the cover’s a little thicker, I’ll throw the ChatterBait,” Martin said. “I’ll approach with the moving bass and then, the jig is going to be the main deal.”

Time of day often dictates bait choices, but Martin stresses the importance of understanding tide progression. Particularly relevant for multiday tournaments, the tide cycle’s nearly one-hour daily advancement can literally define the day’s opportunities.

“If today the mid-to-low outgoing [tide] is at 8:00 in the morning, tomorrow it’s going to be at 8:55; the next day, it’s going to be at 9:50,” Martin said. “At some point, that optimal tide is going to hit at noon, so I might not be throwing a ChatterBait or squarebill; I might go straight to jigs.

“If the mid-to-low outgoing is in the early morning and the fish are a little more active, then they’re going to react to [those moving baits] better. It’s not an exact science; you fish the conditions of the day and the tide that you have. It’s different every day.”

BAIT: ChatterBait

WHY: Moving bait attracts bigger bites

WHERE: Hard cover

Koby Krieger

Kreiger’s home state of Florida, particularly the south end, sees a much earlier spawn than the rest of the country. With nearly year-round warmth creating a much longer spawning window, the year’s last quarter often sees fish on beds. That means the summer/fall transition sees preliminary staging.

“September is still hot, but going into October, it might start cooling off,” Kreiger said. “In south Florida, the first wave can move in by October, so I’ll fish a staging area, like an offshore point of grass or a shellbed, and look for some type of big forage like bluegill.”

Offshore depth may vary from about 5 to 6 feet on Lake Okeechobee to 10 to 20 on the Harris Chain. Regardless of the venue, Kreiger believes he’ll find his best chance of tempting a legitimate giant with a big glidebait like the 6th Sense The Draw in a bluegill color. His second option: a 13-inch Gambler ribbontail worm Texas-rigged on a 5/0 hook with a 1/4- to 3/8-ounce weight.

For his ribbon tail, Kreiger finds the redbug color most productive in deeper water, while junebug excels in the shallower areas. A hopping action allows that ribbon tail to do its thing and trigger reaction bites.

“Water clarity would be the big thing,” Kreiger said of his bait choice. “If I have 2 to 3 feet of visibility, the glidebait would be a great bait to throw. You can fish it through multiple depths in the water column. You can fish it out deep; you can fish it up shallower on top of the water.

“It’s warm and the fish are active, so you don’t have to fish it super-slow. Start with a slower presentation and then pick up the pace until they tell you what they like.”

If he’s fishing the glidebait at a peppy pace and fish are following without committing, throttling back often closes the deal. Conversely, no interest whatsoever tells him he needs to increase the retrieve speed.

“A lot of times, if I have followers that won’t commit, I’ll come back and pitch a drop shot with a 6-inch finesse worm,” Kreiger said. “For whatever reason, morning dawn seems to be the color they like.”

With either bait, Kreiger’s conscious of his position relative to the prespawners. Fishing into the wind, he said, helps him maintain his distance and keep from driving on top of his targets.

BAIT: Glidebait

WHY: Covers multiple depths

WHERE: Staging areas

Joseph Webster

When it comes to whopper Alabama spotted bass, Joseph Webster believes in getting right to the point and using his “top” bait. Enough with the puns — here’s how the second-year Elite hunts his giant bites.

“I would always go to the upper end of a Coosa River [lake], where there’s fresh water coming in, more oxygen, more current,” Webster said. “I would throw a Berkley J-Walker 120 in the bone color, and I’d hit every point up and down that lake.”

Starting with the habitat choice, Webster particularly likes going upriver to find the smaller points and islands where time and current have scoured these extrusions to create ideal ambush spots. Big spots are savvy hunters, so they know well the feeding advantage such places offer.

“A lot of times, you can sit your boat right on that shallow stuff and throw your bait to where it falls off into 4 to 5 feet,” Webster said. “The fish will sit right there kind of hidden and ambush anything that gets into that shallow water. You’re in their house then, and it’s a done deal.”

It’s not rare for a big topwater to attract a striped bass, but while these hefty marauders can burn a lot of valuable time, Webster considers the positive.

“A lot of times on the Coosa River, when you catch big stripes, big spots are hand-in-hand with them,” he said. “A lot of times, there can be several big spots there. They’ll be grouped up in that eddy. When one goes, it’s like the whole party goes with them.

“Plus, those 10- to 12-inch spots won’t be hanging with the bigger spots or the stripes. When they get to the 3- to 4-pound class, they’ll be in little groups.”

As for the bait, Webster wants the largest of the two J-Walker sizes (also a 100) for its water displacement. Maximum display with lots of water displacement, he said, anchors big-fish appeal. Give ’em a good reason to leave their cozy spot and attack.

Using a 7-3 medium-heavy Abu Garcia Fantasista rod and a 7.3:1 Revo STX with 30-pound SpiderWire DuraBraid line, Webster makes the longest casts possible. Retrieve preferences may vary from day to day, so he reads the fish and adjusts to their reactions.

“With that walking-the-dog retrieve, some days it has to be really fast to get them going,” Webster said. “If you work it slower, you miss fewer, but you’ll often see them just following it back to the boat. You have to just see what they want each day.”

As for timing, Webster said, “In the [late summer/fall], morning’s good, but you can catch them all day long. They’re not dumb. They know winter’s coming.”

BAIT: Topwater

WHY: Calls up ambushers

WHERE: Points