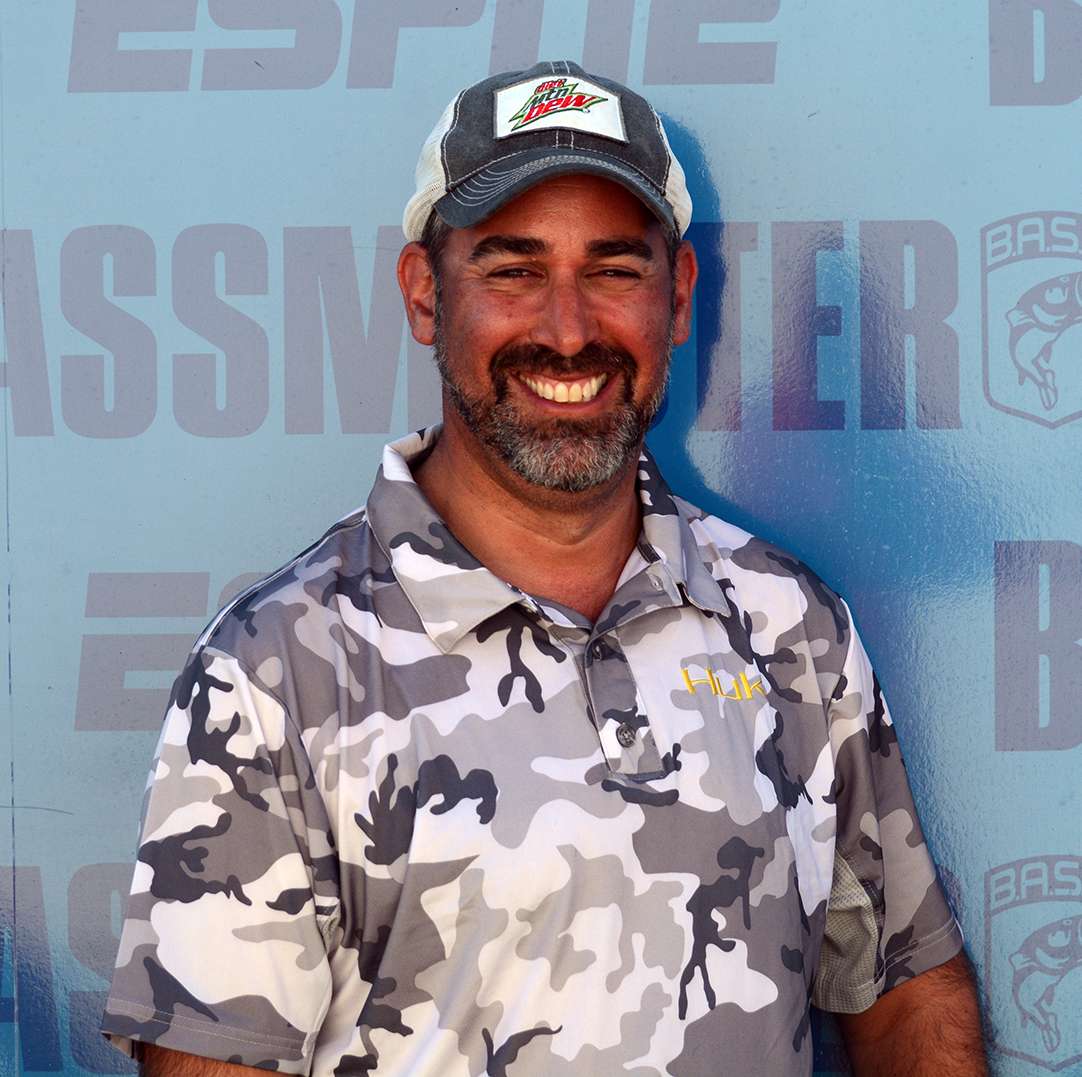

After five seasons away, Jordan Lee is back on the Bassmaster Elite Series, and back on a path to history.

It’s not that he didn’t accomplish much while he was gone. On the contrary, he earned six figures in tournament winnings and finished in the top seven in angler of the year in four of five years on the Bass Pro Tour, including a title in 2020. Rather, he took a substantial detour away from his path to historic, measurable greatness. Success across the two tours isn’t that different, but for purposes of lifetime stats grafting one to the other just doesn’t work. It’s apples and bowling balls, or square pegs in round holes.

When Lee left the Elites, he’d qualified for four straight Classics as a pro (plus one as a collegiate angler), winning two of them consecutively. He’d finished in the money in three-quarters of his Bassmaster events, and in the top 10 in over a third of them. He was already a “BASSillionaire.”

And he was not yet 30 years old.

To put that in perspective, Kevin VanDam had not yet won his first Classic at 30. It took him until 38 to win his second. Rick Clunn, the only active Elite with more Classic wins than Lee, claimed his first Classic trophy a few months after his 30th birthday, and his second a year later. Hank Cherry, the only other active Elite with two Classic victories — and the most recent to go back-to-back — was 46 when he won his first.

Of course past performance is no guarantee of future results, but Lee hasn’t shown any signs of slowing down. Even if he didn’t sacrifice his likelihood as an eventual Hall of Famer, I do wonder what his years away will mean to his legacy at B.A.S.S.

The closest sporting analog I could think of was legendary baseball player Ted Williams — nicknamed the Splendid Splinter. He played the entirety of his remarkably long career (1939-1960) in Major League Baseball for the Boston Red Sox, but missed three seasons during what should have been the prime of his career to military service in World War II, and most of two more during the Korean War. To be clear, I’m not saying that Lee’s time away from the Elites is directly comparable to Teddy Ballgame’s military service — it was a business decision rather than a selfless decision in service to his country — except that the impact could be similar.

Prior to heading off to World War II as a fighter pilot, in four seasons Williams had hit a remarkable .327, .344, .406 and .356, with an average of 32 home runs. Upon his return, he hit at least .342 over the following four seasons, with an average of over 34 homers. After returning from Korea for the 1954 season, he batted at least .328 five consecutive years.

What could he have done with those five prime seasons in the majors? Again, maybe he would’ve gotten injured stateside, or perhaps his time away from the game somehow strengthened his resolve to excel on the field. But the equally if not more likely assumption is that he would’ve padded his already exceptional stats.

Williams was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility, as he should have been, but you can’t help but wonder how much better his stats would have been with those five additional seasons on the field. After all, one of the greatest pure hitters in history, despite a long career, didn’t notch 3,000 hits, stopping nearly 350 short of that mark. He notched 521 homers. With five more years of career average output, he might’ve been in the 700 range. At the time of his retirement, only Babe Ruth had reached that number and Jimmy Foxx was the only other retiree who’d hit more that 521. To date, Williams is still tied for 20th on the all-time list, and only nine batters have hit over 600.

That doesn’t resolve one other “what if.” Pundits often speculated that a one-for-one trade of Williams for Joe DiMaggio (highly unlikely given the fact that the Yankees and Red Sox were extreme rivals) would’ve put a left-handed batter in a ballpark suited for that angle, and a right handed batter in a stadium that was a better fit for him, helping both their offensive outputs. Students of Lee’s career should take note that just as in baseball, in fishing where you compete determines a lot of how you’re perceived.

Indeed, “what ifs” are a big part of what makes sports, including professional fishing, exciting to follow, and fun to argue about in friendly barroom disputes. Lee now returns not as a wunderkind, but as a semi-grizzled veteran of a decade of professional competition. He has the unique luxury of a long runway ahead of him if he wants it, in a sport that doesn’t necessarily have an expiration date. You only need to look at Rick Clunn, in his 50th year of competition — and a two-time winner since 2016 — to see that Lee has ample opportunity to improve his already-impressive resume.

At the same time, there’s a new round of 20-something fishing freaks who are gunning for him, just as he sought to topple the likes of Clunn and VanDam a “fishing generation” ago. Lee has already distinguished himself, but the path to becoming a first ballot Hall of Famer is not yet cleared. There’s no guarantee he’ll ever win another Classic, or an Elite Series event, or an Elite Bassmaster Angler of the Year title, but it would be foolish to bet against him.

He also has a long way to go if he wants to match the Splendid Splinter, because in addition to induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame, Williams is also in the IGFA Hall of Fame. We’ll wait and see if J-Lee can crush the long ball.