When grass mats at the surface, it can create opportunities to catch the biggest bass on any given body of water. Although it’s sometimes difficult to penetrate, the rewards can be huge.

Big bass will hide beneath matted vegetation at any time of the year, especially during periods of extreme temperatures — hot or cold. This carpet-like cover conceals and insulates them. It also provides plenty of oxygen and a steady food source.

There are many types of matted vegetation, and virtually all of them can hold fish. Among the more common are floating plants like duckweed, water lettuce, hyacinths and dollar weed. There are also subsurface varieties that top out on the surface, such as hydrilla, milfoil and peppergrass. As these submerged varieties reach and spread across the water’s surface, sunlight is denied to their lower portions and subsequent thinning occurs. With it, cavernous voids are created. Big bass will find these underwater caverns and thrive within them. Getting to them is the challenge.

Penetrating thick, matted vegetation isn’t always easy — even with an ounce or more of weight. Then there’s the problem of where to start. In many cases, it all looks the same. But we’ll get to that later. First, let’s discuss lure selection.

The proper tools

The most common choice for penetrating thick, matted cover is a Texas-rigged soft-plastic craw or creature-type bait, and there are countless to choose from. My only advice here is to keep them compact. Soft-bodied baits that are oversized or feature bulky appendages won’t penetrate thick cover easily. In fact, you might not get them through at all. So keep the lure body simple and as compact as possible.

I prefer small craws and tubes designed for flipping, as they tend to slide right through the mat unhindered. I pair them with just enough weight to penetrate the cover — no more. The standard rule is: Use only the amount of weight necessary.

I use tungsten exclusively. Tungsten is much heavier than lead by volume, so less of the material is required. That means your lure and presentation will look much more natural and appealing to the fish. The last thing you want is a bulky, oversized lead weight. Those will sometimes jackknife to one side, causing the lure to fall unnaturally through the water column. Even when they fall correctly, the mass of such a large weight can discourage fish from biting or holding onto the bait. They can also interfere with hook penetration by prying the fish’s mouth open.

When it comes to hooks, there are two schools of thought. Some prefer a traditional straight shank, J-shaped hook, others like an extra wide gap (EWG) hook. Those who opt for the straight shank often tie it on with a snell. While I use both style of hooks, my preference is for the EWG.

Regardless of which type hook you choose, be sure it’s a forged, heavy-duty flipping model. Thick cover will test your tackle, and the last thing you want is a point that curls or a shank that bends when trying to wrestle big bass from heavy cover.

Although soft plastics are the popular choice for punching matted cover, don’t discount jigs. Paired with the right trailer, flipping jigs can be deadly beneath matted vegetation. And they’ll oftentimes catch the biggest fish.

There are many makes to choose from. Just be sure they have a strong, forged hook with a super sharp barb. Then it’s only a matter of pairing them with the right soft plastic trailer. Most often, I’m using the exact same craws and creature-style baits as I would on a Texas rig.

Having the right lures is important, but so is presenting them with the right tackle.

For that, I use a stout Shimano Expride 180H+, 8-foot punching rod — my favorite because of its tip action and backbone strength. It’s also super light for its size, which is critical when flipping nonstop for eight to 10 hours a day.

I pair my flipping sticks with Shimano Curado 200XG or Bantam 150XG baitcasters because — like the rod — they’re light and strong. I spool them with 40- to 65-pound braid, depending on the density of the cover or the size of the fish I’m dealing with.

When the bite gets tough, I either downsize to 30-pound braid or add a length of fluorocarbon leader in 20- to 25-pound test.

What to look for

When I approach a mat, I always consider the edge first. Many times, bass will hold there, anticipating their prey to swim within range. By pitching to the edge from a distance, you’ll know whether or not to move closer. Note: Pitching to the edge may require a lighter setup, as the fish will get a better look at your bait and line. You don’t want anything to appear unnatural.

If they’re not on the edge, my next flips are several feet inside. I look for unique features, such as small points or indentations along the edge to target first. A mix of cover types can also be key — such as where two types of grass come together to create a seam, or where hard cover like wood and rock exist. Bass will find these combinations of cover and relate to them.

Something else to look for are thinner or thicker areas in the mat. Even taller vegetation, like mature hyacinths, can draw bass like a magnet. And don’t forget duck blinds. Hunters frequently build them in fields of topped out vegetation, and bass will use them like a dock on an otherwise bare shoreline.

If I’m not connecting with fish within a few feet of the mat’s edge, I’ll move further into the interior — sometimes 10 to 15 feet or more from the outer edge. Although this sometimes is a tedious process, it can put your lure where no one else is fishing.

Tips on touch

When my lure passes through the cover, I always let it freefall at its own pace. The only exception is when yo-yoing the lure is required. Then I may control the sink rate. Otherwise, the speed at which it falls is determined solely by the weight of the sinker and friction on the line as it passes through the canopy.

Again, the rule of thumb is to use only the amount of weight necessary to penetrate the cover. Any extra will usually work against you.

Bites can come at any point during the bait’s descent. If the fish are aggressive, they’ll usually strike just as the lure breaks through the mat. In fact, big fish will sometimes help it through by sucking it under. You’ll see the mat raise slightly, then, like a vacuum, it will sink as your line gets tight. There’s no better feeling in flipping.

When fish are less aggressive, they usually take the bait off the bottom — sometimes requiring a bit of coaxing. After letting a bait fall freely to the bottom, if I don’t detect a strike, I’ll raise the line slightly — just enough to make the bait move in place. If that doesn’t work, I’ll hop it once or twice. If that doesn’t provoke a strike, then I’ll usually retrieve it for another presentation. The only exception would be if I’m certain fish are holding where I’m presenting the lure, or under cold front conditions where dead-sticking may be required to get a reaction.

When I hook into a big fish, I try to keep its head up and coming my way. Where some anglers get into trouble is when they try to winch the fish completely out of the cover. Although you can sometimes get away with it, too often it leads to lost fish. Remember, you’re using braid and a very stout rod. If something gives, it’s likely to be the fish’s flesh.

My approach is to try and bury them in the cover at the surface. I have no idea why, but when I’m able to get a fish wrapped up in thick weeds, they almost always quit fighting. Then it’s just a matter of going to the fish and digging them out.

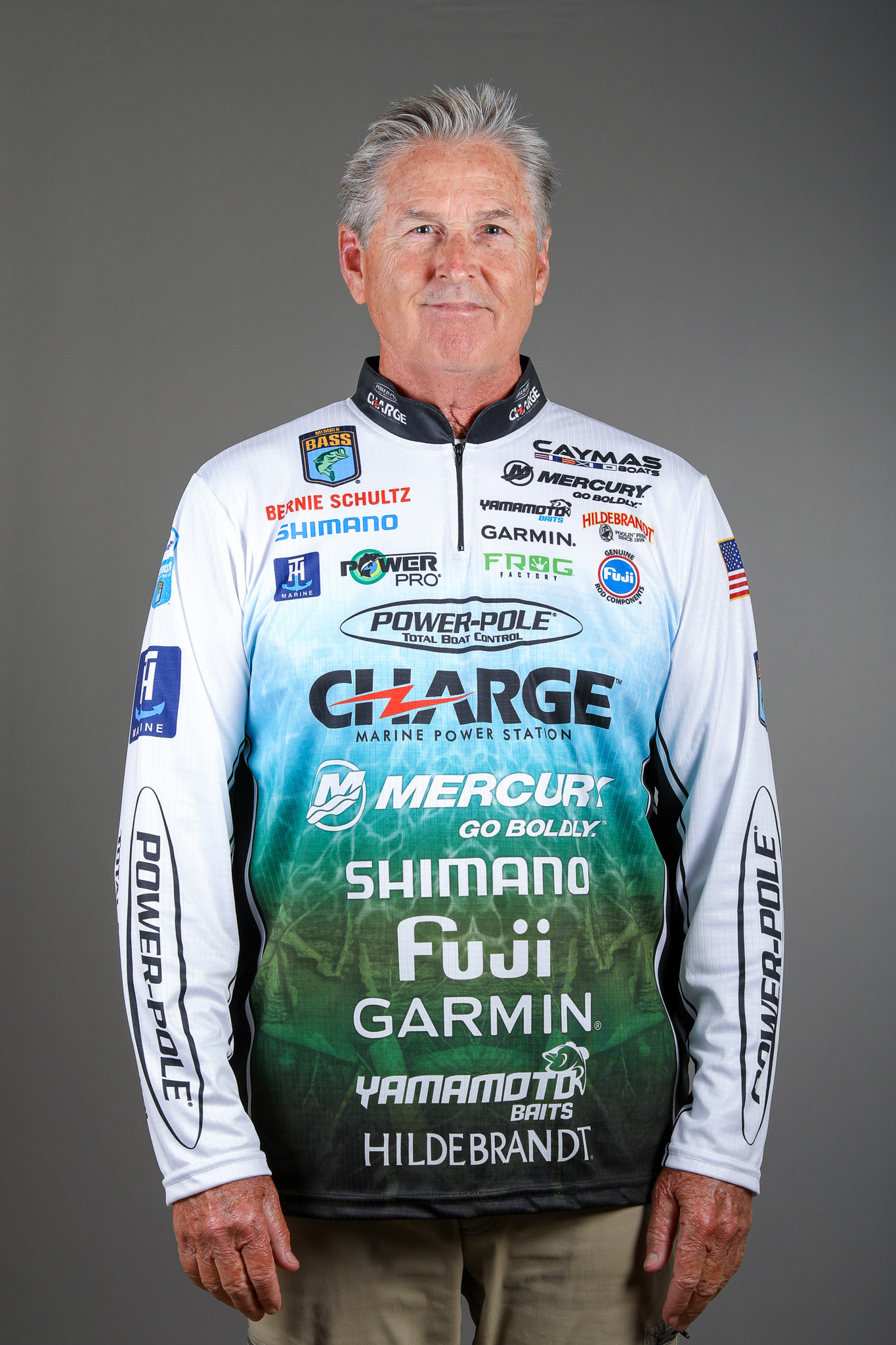

I can’t tell you how many monster bass I’ve caught this way — including several taken in tournaments that weighed 8 to 10 pounds. It’s also how I caught my personal best bass, shown in the photo above. Hopefully what I’ve shared here will help you do the same.

Follow Bernie Schultz on Facebook and through his website.