Chris Armstrong, a longtime illustrator for Bassmaster Magazine, died April 23, 2014, after a lengthy illness. His illustrations were known throughout the bass fishing and hunting world. You can see a selection of his artwork here. The story below, originally called Drawing Bassmaster‘s Playbook, was written in May 2008 by then-editor of B.A.S.S. Times Matt Vincent, who worked with Armstrong and was a close friend of his for decades. Armstrong was 66.

———————-

Every sport requires a playbook. Whether it’s how to run a full-court press in basketball or how a quarterback connects with a wide receiver on a post pattern, success requires a game plan.

There was a time when there was no playbook for bass fishermen. Fishing wisdom traveled through the grapevine and the best lessons came with crude drawings on cocktail napkins.

Knowledge was not widely available prior to the introduction of Bassmaster Magazine, the playbook that eventually educated an entire generation of bass anglers. Part of the B.A.S.S. plan, of course, was tournament competition, which functioned as the proving ground for fishing techniques and strategies.

But playbooks need charts and diagrams. What was needed was someone capable of turning cocktail napkins into works of art.

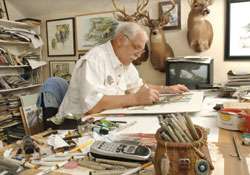

In a quiet suburban neighborhood in Jacksonville, Fla., on a typical day inside Smackwater Studio, Chris Armstrong interprets our sport through his illustrations and art.

For more than two decades, Armstrong has added the third dimension, whether it’s for “A Day on the Lake” or the winning patterns of the pros.

Smackwater Studio is a sportsman’s art gallery chock-full of Armstrong originals. Every type of game that sportsmen pursue from the Florida Keys to the wild rivers of British Columbia is on display. Your eyes are drawn to dozens of portraits of black bass, tarpon, king salmon, catfish and whitetail deer that have appeared — or will soon appear — in sportsmen’s magazines, travel publications and books.

Peering over Armstrong’s cluttered desk are several whitetail mounts. Above the studio’s entryway is a hideous stuffed goat head. Missing from the well-traveled Nubian are several clumps of hide and part of an ear.

“That came from a garage sale,” he grins. “My wife (Pam) wants me to get rid of it, but I can’t bring myself to throw it away.”

The glassy-eyed goat never blinks.

In the background, the growling sounds of Leon Redbone waft from a small stereo barely visible between stacks of artwork, strange mementos from the 1960s and piles and piles of art supplies. Prints and paintings lean against file cabinets. On the wall next to his desk are several caricatures of the late Hunter S. Thompson done in the signature style of Ralph Steadman. Beside them are several Picassos and a very good Rembrandt, prompting the visitor to ask: “Are those real?”

“Sure they’re real,” Armstrong smiles. “I did them myself.”

The 59-year-old Florida native is one of the most talented and prolific wildlife artists in America. And like most artists, there are the expected eccentricities — a Mr. Natural cartoon, a bottomless coffee pot and the gaping mouth of an alligator.

The wild side of Armstrong, his sometimes irreverent sense of humor, is evident in B.A.S.S. Times every month, in fact, supplementing the columns of B.A.S.S. senior writer Don Wirth, another old hippie who has found his niche in the B.A.S.S. family.

“I’ve still got the one [illustration] that didn’t make it past the ESPN lawyers,” he smiles, pointing with a great sense of pride to a cartoon-like rendition of rap star Snoop Dogg.

Okay. So how did Armstrong find his niche?

As he tells it, “accidents happen.” But not in those exact words.

While working as an illustrator for the Jacksonville Times-Union in the late 1970s, Armstrong was asked by the newspaper’s outdoor editor, Bob McNally, to illustrate an article about deer hunting tactics for Southern Outdoors, a now-defunct magazine that was part of the B.A.S.S. publishing group.

“I looked at the outdoor stuff no differently than I did the usual editorial work, whether it was an editorial cartoon or a basic diagram,” remembers Armstrong.

McNally asked Armstrong to provide a visual diagram to show how deer move in relation to topographical features. Armstrong handed the completed artwork to McNally the next day.

When the editorial package arrived at Southern Outdoors, Armstrong’s art grabbed the attention of Dave Precht, who was editing the magazine. “As soon as I saw it, I knew Chris Armstrong and I would be working together regularly,” remembers Precht.

When Bob Cobb left Bassmaster Magazine to produce The Bassmasters television show for TNN in 1984, he handed the editorial helm over to Precht, who brought with him some of the talent he had assembled at Southern Outdoors.

Atop the list was Armstrong.

“He can read a manuscript and churn out images that tell the story almost as well as the words,” says Precht. “He’s the answer to every overworked editor’s prayers.”

Once Armstrong’s work began to appear in Bassmaster on a regular basis, it also grabbed the attention of other overworked editors in the business, and his phone started ringing.

And overworked editors weren’t the only ones to notice Armstrong’s talent.

Last year, Armstrong completed an elaborate walking mural at the headquarters of the federal estuarine research reserve at Guana Tolomato Matanzas on Florida’s Atlantic Coast. And earlier this year, Armstrong received a commission from the state of Florida to create another mural, one that will detail the pre-Columbian lives of American Indians who lived near Okeechobee and the world in which they lived.

The national exposure he achieved through Bassmaster eventually closed his newspaper days and opened the doors of Smackwater Studio.

“It definitely was the biggest break I’ve had in my career. It allowed me to go full-time freelance.”

Ultimately, what makes Armstrong’s art unique is his knowledge of nature. Growing up in Florida, Armstrong spent most of his youth exploring the coastal and inland waters of central and northern Florida. He studied the details of the plants and animals around him, the landscapes and the rivers and streams. He examined textures and studied light and shadows and watched how creatures moved and related to their environment, whether it was a heron standing along the shore or the way trees bend in the wind.

“I was always interested in the small things, the stuff you don’t normally see. And I was always drawing that kind of stuff. We had a set of World Book encyclopedias and I think I went through all of them, page by page, at least a dozen times or more.

“I used to get every copy of Life magazine I could get my hands on. And I also got some of the old Life books, too. Any kind of research material I could get a hold of was something I would pore through.”

That youthful interest in art became his career. Armstrong earned a degree from the Ringling School of Art in Sarasota, Fla., and his first job out of college took him to Kansas City, Mo., where he created greeting cards for Hallmark. He eventually returned to Florida and began working for several newspapers in the Sunshine State before his break with Bassmaster happened.

Although he’s an avid fisherman, some of Armstrong’s assignments include other species of wildlife not native to his home state, game animals he’s never personally encountered in the wild — antelope, mule deer, elk and moose. So how does an old, self-described hippie from Florida capture them so vividly with his pens and paints?

A vivid imagination, Armstrong says with a smile.

Closer to the truth, it’s artistic talent and research.

“I rely on scientific books and wildlife reference sources. What I’m not familiar with, I learn. And what I don’t know, I ask.”

On this day, he’s putting the finishing touches on another elaborate piece of art, an underwater scene of a largemouth bass that is peering upward. Like the bass, your eyes are drawn to the topwater lure above it. You feel the explosive energy of the fish about to be unleashed, frozen in time by Armstrong’s ink and paint.

“You have to show wildlife in its natural habitat. As an artist, you have to be real because fishermen will recognize a fake. You have to show what’s there. Really, that’s the job of an artist — to show things how they really are.”

And very few wildlife artists have ever done it better.

Acquiring an ‘Armstrong Original’

Every avid hunter and angler in America has seen the art of Chris Armstrong.

Over the past 30 years, his work has appeared in virtually every major outdoor magazine in America, including Bassmaster, Field & Stream and Outdoor Life, to mention only a few. And his artwork has been used by several outdoor manufacturers, including Realtree, Pure Fishing and Top Brass Tackle.

Due to a growing demand for his art — not only for its aesthetic value but also as a financial investment — Armstrong has decided to make his private work available to the public through a series of signed and limited edition wildlife prints.

In addition to a beautiful “Black Bass Series,” Armstrong is also producing sets of limited prints ranging from “Whitetails” to the “Wild Turkey Grand Slam.”

Each print is available for $150 “while supplies last,” according to Armstrong. Once the final print in each series has been sold, the template will be destroyed to ensure lasting value for each print.

For information on how to purchase these Armstrong originals, contact Smackwater Studio at 904-519-0021 or e-mail smackwater@comcast.net.